2023 – The Year of Crashing Grades at A Level?

The UK’s Centre for Education and Employment Research (CEER) at the University of Buckingham has predicted that A Levels students are facing a seismic hit on grade expectations this year after failures to adjust grades sufficiently in 2022. 100,000 plus students will have been impacted by a drop in grades if the UK government succeeds this year in returning to the Pre-Pandemic grade levels of 2019. In 2023, this means we are looking at more than 60,000 students globally potentially facing a hit.

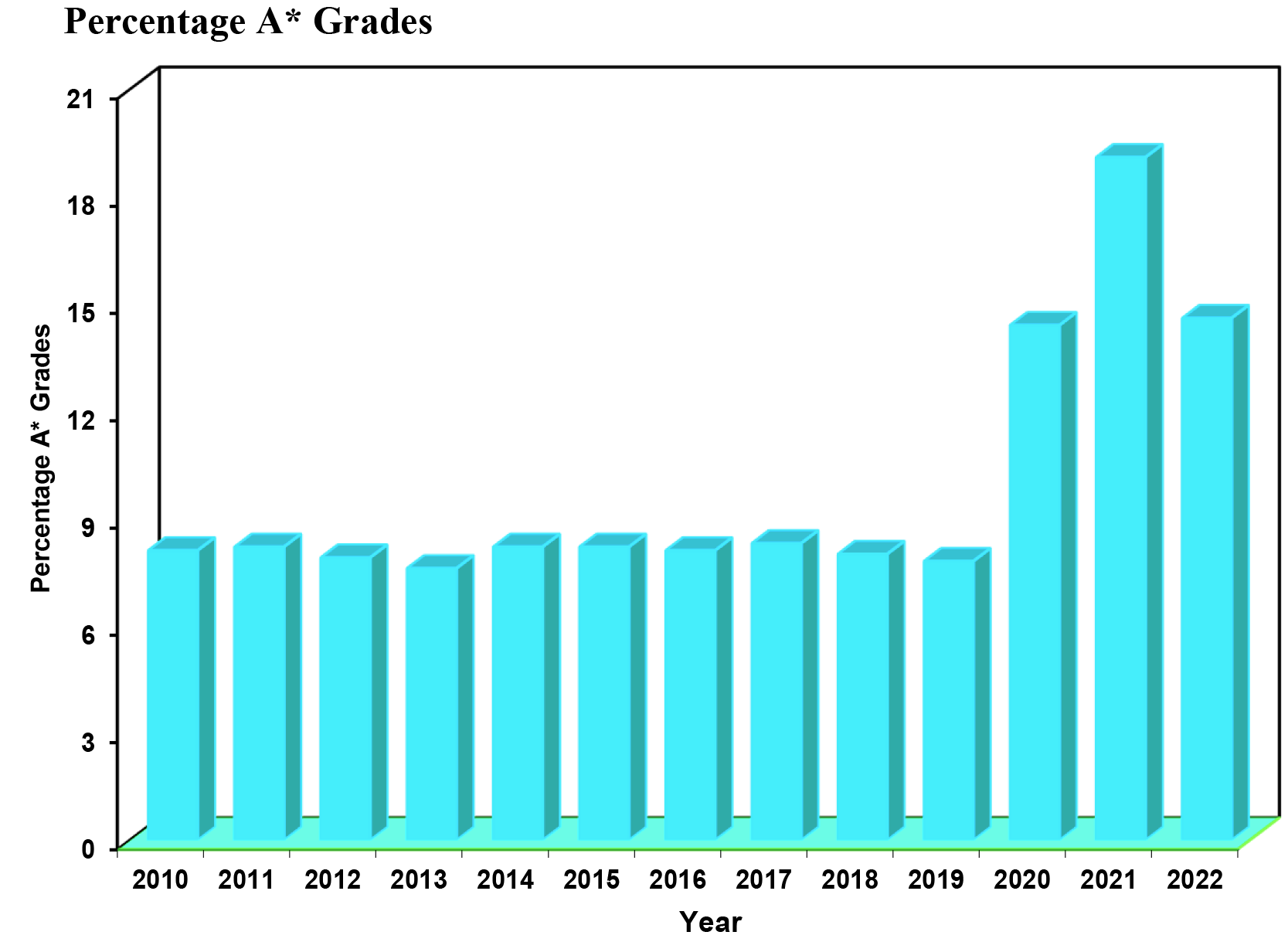

“Taken together the two years of teacher assessment, 2020 and 2021, the percentage of A* grades almost trebled from 7.8 to 19.1, and A*/A grades nearly doubled from 25.5 to 44.8. In other words, an extra 100,000 A* were given out in 2021 compared with 2019, and an extra 168,000 of A*/A grades.”

CEER. 2023.

Research by the CEER said: “Assuming a reduction in two subjects per person, this would mean about 30,000 students not getting the A* grades they could have expected last year, and nearly 50,000 not getting the A*/A grade.” The CEER believes that this push to crash grades is just too far too much too soon.

“To achieve this in two years is brutal, because it shatters the over-optimistic impressions that the grade bonanza created.”

CEER. 2023.

Back Story – Grade Inflation in British Education

The A* Grade was introduced in 2010 to manage grade inflation of 27% in the awarding of A grades at A Level. In 1985, some 9.5% of students secured an A grade. By 2010 this had risen to the point that 27% of students achieved A grades. With the introduction of the A* grade, the levels dropped back so that, between 2010 and 2019, around 8% of students consistently achieved an A* grade.

In 2020 the number of students achieving an A* grade near doubled to 14.4%

In 2021 the number rose again to 19.1%.

In 2022, the government asked for the percentage of students achieving a Grade A* to drop to a half-way point of 13.5%. But….this target was missed last year, with the number dropping to only 14.6%, a reduction of 4.5%. As a result, a much bigger drop of is now required this year from 14.6% to the 7.8% benchmark established in 2019, a drop of almost 7%, if the UK government’s target is to be met.

Graph showing the “explosion” (CEER) of A* Grades between 2020 and 2022. 2022 was designed as the first step in reducing grades to the level of 2010-2019 but as the drop in 2022 was smaller than predicted, students in 2023 are expected to take a hit.

The same inflationary story applies to A grades. Until 1985, less than 10% of students secured an A grade. By 2027 the number rose to 27%. After the independence of Ofqual in 2010, the rate settled at round 25% of students securing an A grade.

“With the last-minute switch to teacher assessment in 2020 all this careful structuring broke down.

“A-grades went wild.

“The 25.5 per cent awarded in 2019 became 38.6 per cent in 2020.

“In 2021 there was more time to prepare for teacher assessment and for it to be made more systematic, so one might have supposed grades would fall. But quite the opposite occurred.

“A*/A grades increased even more, so nearly half of all entries were given a top grade (44.8 per cent) that year.”

CEER. 2023

The Impacts of the Covid Years on Girls and Boys

Girls were significant beneficiaries of the Covid Years too between 2022 and 2023 as practical, more “subjective” subjects depended more significantly on teacher-assessed grades.

“In music the percentage went up from 19.3 to 54.8, in drama from 18.0 to 48.8, and media studies from 11.00 to 29.6.

“In 2022, with the exams back in place, there were still more A*/A grades in music and performing expressive arts than in physics and chemistry.”

CEER. 2023.

The Covid years switched the gender balance significantly in favour of girls at the highest grades:

“Girls leapt ahead by 3.2 percentage points in 2020 and 4.8 percentage points in 2021, the biggest ever gaps between the sexes at this level. More than that girls were ahead at A* in 2021 in all but three of the 38 A-level subjects.”

CEER. 2023.

With the ending of teacher-assessed grade in 2021,and return to exams, the boys’ share of top grades trebled.

CEER believes that the Covid changes are going to be hard to undo because in these subjective subjects “[a] profound change in the mind-set seems to have taken place. If this survives the return to exams, it will make it difficult to get A*/A grades back to their former levels.”

“The maths is straightforward, how feasible will it be to put it into practice? Teacher assessment has given subjective subjects a taste for awarding top grades, which they will be reluctant to relinquish.

[…]

We see how Ofqual and the boards have resolved the dilemma on the 17 August. But I suspect that they will not be able to get the grades all the way back to where they were before Covid.”

CEER. 2023.

Nevertheless it is expected to see boys benefit from the return to their traditional lead over girls in securing the highest A* grades, particularly in Mathematics and the Sciences, given the UK government’s mission to remove grade inflation.

Subject Prejudice and Gender Inequality

The question mark remains over whether it is even possible now to cut grades in the more subjective disciplines. Many believe the bhorse has bolted in a system that is weighted against girls. Boys also suffer in our exams focused system too. They achieve high marks predominantly because they gravitate to just five subjects – Mathematics, Further Mathematics, physics, chemistry, and economics. In 2019 just these five subject contributed two-thirds (65.5%) of the A* awarded to boys.

There are then big questions to be answered about a system that inherently favours boys – or one in which “objective” subjects are favoured over their “subjective” counterparts. This certainly fits a history of patriarchal social injustice and current UK government aims to reduce funding for any subject that does not eventually lead to high salaries. The current UK government sees little value in the Arts and Culture. Is this the sort of world we want to live in?

Because grade inflation was felt so much more strongly in subjective subjects, the issue of such a fast reduction is not only one of being an attack on girls, but also a much broader issue of ethics. As the CECR say:

“To have the blow falling mainly on the subjective subjects may well be questioned as unfair.”

The issue is long-standing. Girls, all things being equal, achieve better than boys. The higher grades achieved by boys in the Sciences skews this fundamental reality – and it is girls that are paying the price.

The Rise of Social Sciences – Against the Odds and UK Government Diktat

If there is a positive, it is that Social Science subjects like Psychology have grown in prestige despite this. Today, Psychology A Level is the second highest subject for examination entries after Mathematics. There are significant increases too in the numbers of students sitting for Political Science and Sociology – subjects that link the Arts and Sciences and aim to answer fundamental questions in a world becoming increasingly incomprehensible as social, religious and historical mores collapse. British students, and many schools, in particular, are defying the push to the Sciences – but, unlike the IB, where languages are mandatory, the interest in both English and MFL is also in decline. The CEER writes:

“I would only point to the great growth of the social sciences coinciding with universities becoming known as hotbeds of activism and wokery.”

It is hard to read whether this is a statement of fact or prejudice, but in our view activism and wokery are the hallmarks of a system that is actually working well and should be applauded. If young people did not question everything we would be asking why.

Areas of the world like the UAE, which still study for AS Levels, are expected to be hit much harder too, as grading in these subjects is more generous and these were used by teachers to justify higher grades in the Covid Years.

Whilst the CEER does not address international students, including those in the UAE, it does also highlight how Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland students are performing differently. Because responsibility for exams is devolved, these governments have been much kinder to students. The lesson for students in the UAE is that awarded grades at A Level are not all the same and vary depending on where they are awarded.

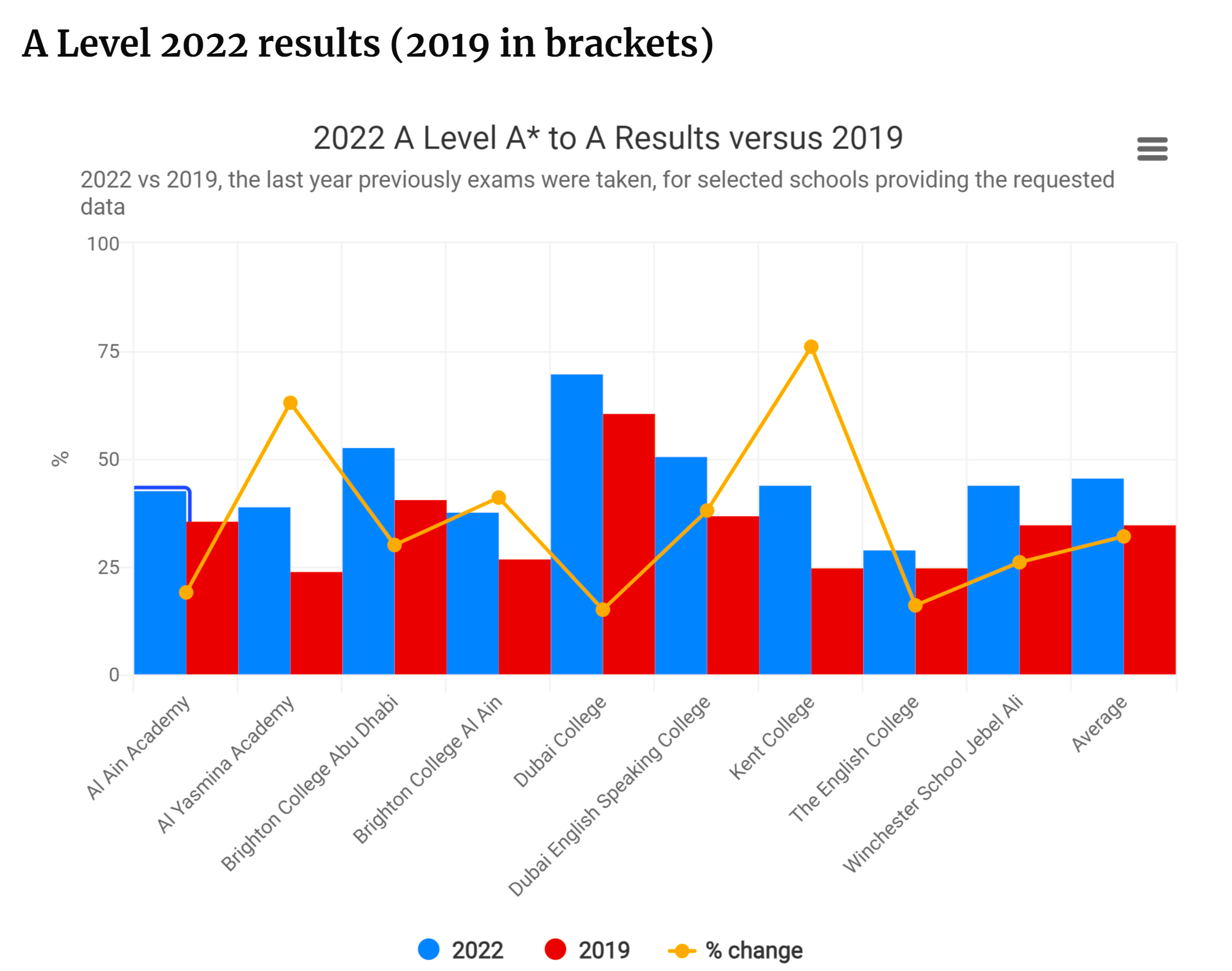

The Lessons for UAE Students – Another Sting in the Tail

UAE students are facing broadly the same challenges as their UK counterparts. Even our most outstanding schools suffered in 2022 – and on the basis of the predictions here, we can expect the hit to be even more profound this year.

Yet there remains some hope that the UK government, or more likely the Examination Boards, will modify their position. Professor Alan Smithers, the director of the CEER, said:

“My view is that the percentages of top grades will be reduced, but not to 2019 levels, because of the pain and upset it will cause to students and parents, because only England of the three administrations is seeking to do it this year, and because of the wider spread of A* across subjects, some of which used to have a lot, and others which didn’t.”

The question remains whether this predicted softer approach will port across to international students, and international Examination Boards. Even if does, however, we can still expect significant reductions in grades to around the percentage level we saw last year. There will still be pain, on the balance of best possible outcomes, but not as much as the UK government has been pushing for. Girls are likely to still bear brunt of these.

There is, however, another sting in the tail. The number of places available at UK universities in clearing this year is limited. Students able to pay international fees may well find more doors open as UK universities fight for valuable external fee income, but those with home status are likely to struggle – and particularly with Russell Group Universities which are all but full. We will be publishing our Guide to Clearing shortly.

What all this means is that we are all going to have to brace ourselves.

Parents and schools will need to be ready to support students both emotionally and practically. Much of the work on how to best navigate clearing is already in place in schools – but with much greater investment this year. Schools know too well what they are potentially facing.

The UK government, on any rational standard, is pushing too far, too fast – but even if the Exam Boards defy them, we must expect grades to take a hammering.

Finally, we need to understand, collectively, that the harshness likely to be felt this year is the fault of the UK government alone, and absolutely not of students, teachers, parents or schools. Students this year, as every year, should be celebrated for their achievements.

No ifs, no buts.

Further information

Join us for GCSE, BTEC and A Level Exams Week. British School Exams Week on SchoolsCompared.com begins on Wednesday 16th August 2023 and continues through to Friday 25th August 2023.

Learn about the official position on GCSE, BTEC and A Level Results in 2023 here.

Advice for Clearing can be found here.

Read the full CEEC report below:

A Levels Grades Collapse 2023

If you would like to comment please forward your thoughts to [email protected]. We aim to include all comments in our British School Exams Week coverage.

© SchoolsCompared.com. A WhichMedia Group publication. 2023 – 2024. All rights reserved.

Leave a Response