Oracy. An Introduction.

The potential capacity for words, and the ideas that flow between them, to have an impact on us is often taken for granted. We have all read a book and come away moved, or in some way changed in our views or outlook on the world. But words on a page are different to the spoken word. Those same words, delivered by somebody who inspires us to believe in what they are saying, can result in a call to action. The spoken word, and the arguments, passions, convictions carried with it, has the power to drive us from complacency to action.

One of the differences is that books do not speak back to us. They take us on a journey that is constrained by the author; we do make it our own, but the journey has a set beginning, middle and end. Life, compared with books, is much messier. Our lives are made as they happen and flow – there are few set endings or even ways of travel. Those who master language and communication, can make the world around them like an artist with a brush on canvas. They can convince individuals or whole nations to change their lives. Oracy is the tool to become powerful and wield power. Oracy is the tool to gain a powerful voice in a world that would so easily, without it, never listen to you.

History is filled with those individuals gifted in oracy that changed everything by bringing people with them on a journey – for good, or for bad. The gifts of oracy – to create strong arguments; to make people understand; to be able to respond to positions held by others that you agree with, or disagree with; to bring people with you on a journey; to inspire loyalty, to make others laugh, or cry; to make others believe in something – or you; these are the gifts all businesses look for in their staff, and we look for in others. Great Oracy requires all the gifts we have as human beings from intelligence to being able to listen to others and respond to them coherently, from empathy, to the ability build bridges between hostile positions.

The importance of Oracy is captured so well in the often-quoted justification for marketing. You can build the most beautiful building in the world or invent a new drug that could save a million people, but if no one knows about them, and, equally, if people don’t believe in them, to all intents and purposes neither exist. In Field of Dreams, the message is explained as “if you build it, they will come” – but in the real world, without oracy, they simply would not. Being accomplished in oracy is to have the power to speak with others beyond the echo chamber of our own internal voices. It is to have the power to make the world in real time. Human beings are social creatures, but without the tools to be social, intolerance, or much worse, soon follows.

In 2023, the UK’s Labour Party announced that it would transform the education sector when it took power by bringing oracy into every school and making it fundamental to the way children are educated. It is seen, by them, as the single most important means of transforming the life chances of every child and making education work properly for every child. Their belief in the power of oracy could not be stronger and the stakes could not be higher. Their future education policy, and the lives of a generation of children, depend on it.

In the UAE, the Oracy “agenda” is in no small part being driven by the extraordinary evangelism of Oracy by Sarah Lambert, Specialist Leader of Education at Dubai College. Mrs Lambert’s belief in the capacity of Oracy to truly empower children – and give them the tools to create an accomplished life, has both transformed Dubai College, and impacted on countless schools beyond its walls.

The following interview with Mrs Lambert provides an insight into her story, one which celebrates the extraordinary impact of Oracy in education, and showcases how UAE education is stealing a march on what is very likely to be the key defining innovation in education policy of the next British government.

Johnathan Westley. Managing Editor.

What is the definition of oracy?

What is the definition of oracy?

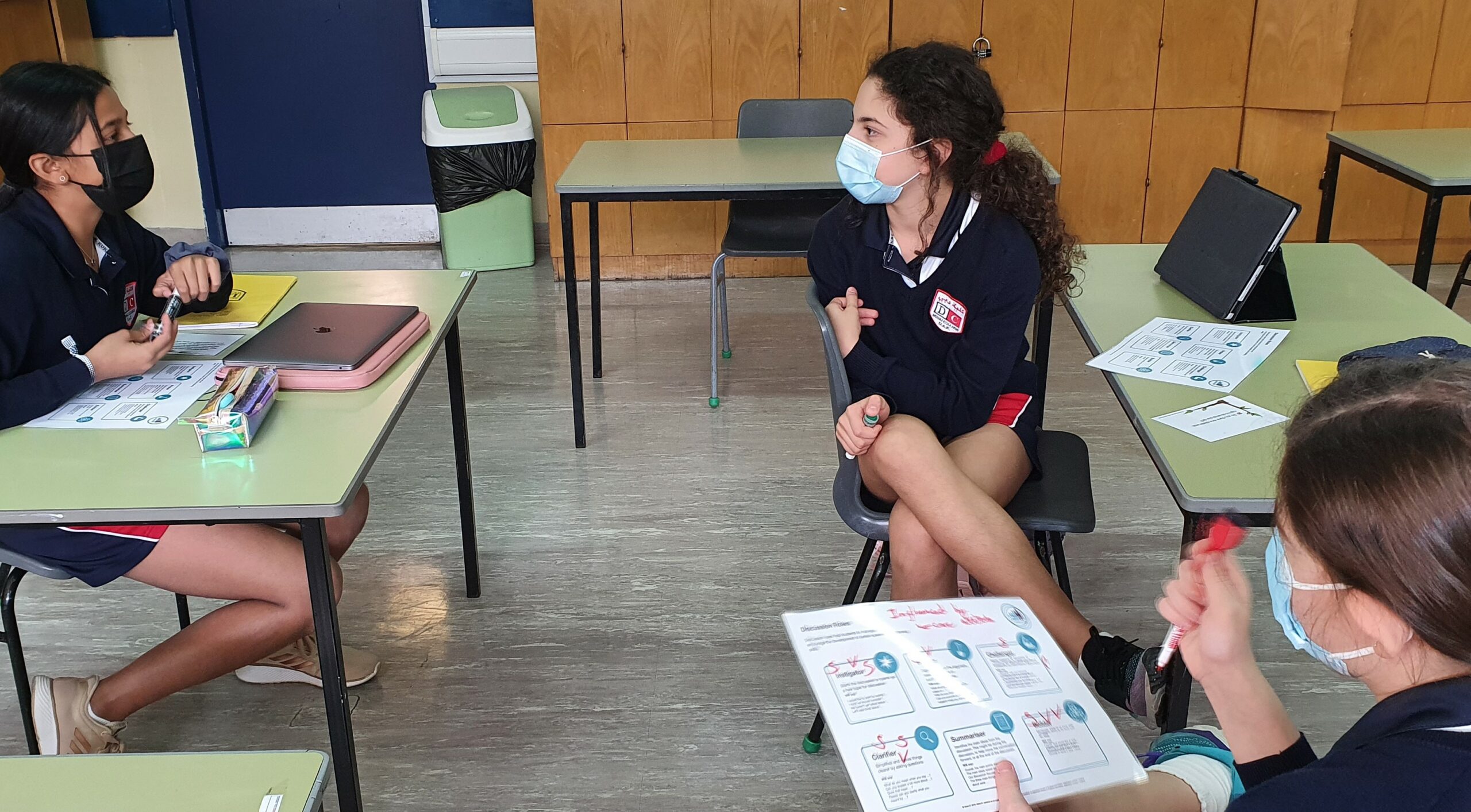

A lesson at Dubai College capturing the application of oracy in the classroom

![]() Sarah Lambert: There are plenty of ways to define oracy, but I think the ESU (English Speaking Union) defines it well:

Sarah Lambert: There are plenty of ways to define oracy, but I think the ESU (English Speaking Union) defines it well:

‘Oracy is to speaking what numeracy is to mathematics, or literacy to reading and writing. In short, it’s nothing more than being able to express yourself well. It’s about having the vocabulary to say what you want to say and the ability to structure your thoughts so that they make sense to others.’

Essentially, it’s about communication – in a fractured world full of tensions, equipping our young people with the ability to listen and communicate with others clearly and effectively, not only empowers them and ensures that their voices are heard, but hopefully fosters respect and greater understanding of differences.

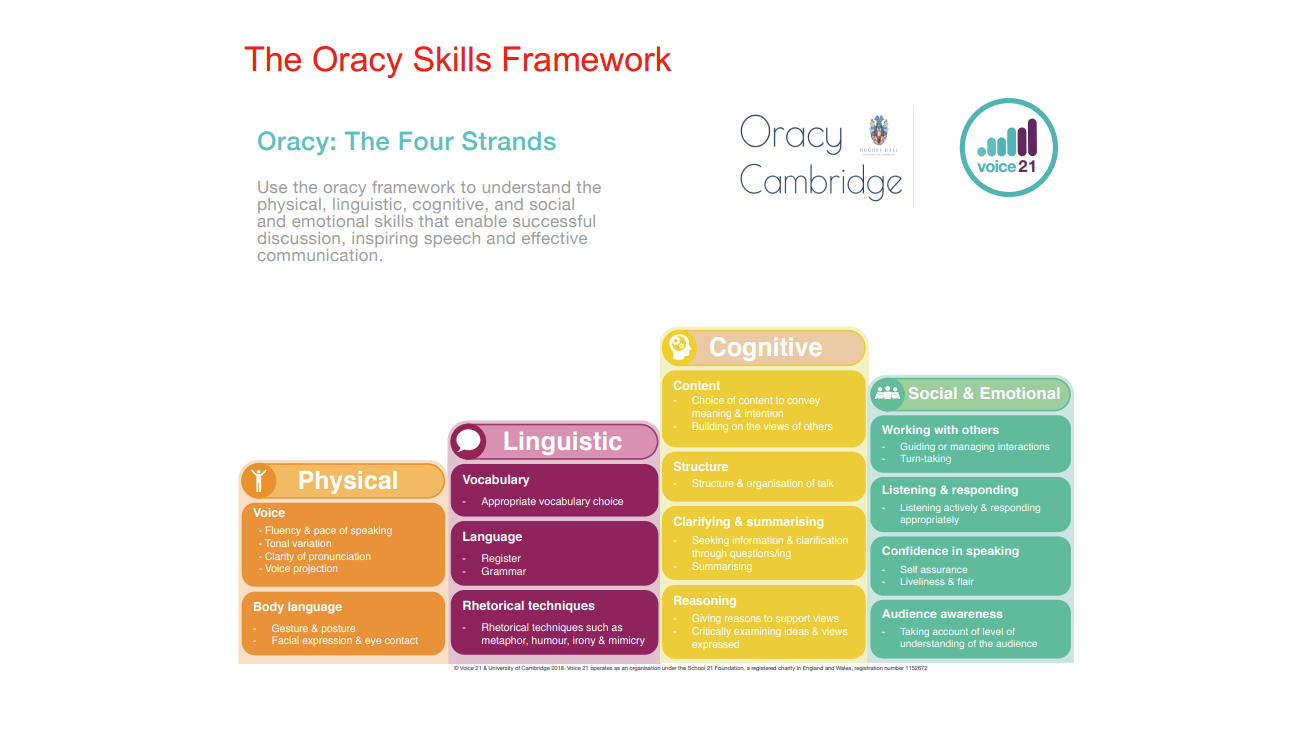

I also like this diagram that Alice Stott and Amy Gaunt include in their book Transform Learning and Teaching Through Talk: The Oracy Imperative (2019, p.19):

I use this diagram a lot with staff, students and parents because it emphasises that oracy is more than just talk. Oracy is the cross over between knowledge acquisition through dialogue, as well as a skill that can be taught/learnt.

There is a caveat though; too often some of our students and parents look to public speaking as the pinnacle of oracy, seeing it as a performative skill. That is not how we are driving and developing oracy though. We see oracy as a collaborative process; a means to learn through talk, a shared enterprise, rather than a solo performance, or a combative debate.

Of course, giving a talk and having a debate are elements of oracy which we include in our learning and teaching – but our main drive is one of dialogic learning, talking with others is a skill that does need to be taught. Students need to be taught how to talk effectively and productively as a collective.

Please provide us with a list, in rank order, of the top skills you can teach a child and include in that list oracy. Can you stop the list when you reach Oracy.

Please provide us with a list, in rank order, of the top skills you can teach a child and include in that list oracy. Can you stop the list when you reach Oracy.

![]()

- Curiosity

- = Respect for others

- = Self-respect

- Oracy

Given that children learn to speak before they can read and write, oracy is arguably the first skill a child is taught. However, I would argue that initially the skill is speech, rather than oracy. Oracy encompasses listening and cognitively shaping ideas to communicate orally, so it’s a skill that relies on a child’s curiosity to communicate beyond innate demands or expressions of needs – and it necessitates both respect of others (so that views can be heard and acknowledged, even if disagreed with) and self-respect (because a child needs the courage of belief in their own views and thoughts to share them with others).

Numeracy and literacy follow immediately after oracy, but I think it’s easy to forget that oral communication is the first thing most children are able to do. It is easy to forget this because, as children get older, their voices become quieter, both metaphorically and literally. I wholeheartedly agree with Britton that ‘reading and writing float on a sea of talk’ (see “Further Information” below).

What is the history of Oracy at Dubai College? How important is its role in the school today? Do you conduct any outreach work to inspire other schools in the importance of Oracy?

What is the history of Oracy at Dubai College? How important is its role in the school today? Do you conduct any outreach work to inspire other schools in the importance of Oracy?

![]() An explicit focus on oracy at DC has developed in two waves. Many of our staff were dialogic practitioners by nature so it was not something that did not already exist; it’s just that our explicit focus upon it, over time, became more strategic and embedded across departments and key stages.

An explicit focus on oracy at DC has developed in two waves. Many of our staff were dialogic practitioners by nature so it was not something that did not already exist; it’s just that our explicit focus upon it, over time, became more strategic and embedded across departments and key stages.

Our first wave started back in 2017-18 when we first introduced the Harkness pedagogy. This was in response to research I had conducted as part of my MSc Learning and Teaching where I had been looking at perceived passivity in KS4 students and I had explored flipped learning to increase student ownership of learning. In doing so, I became aware of Harkness and, following a visit to Wellington College (UK) with Joe Almond (a Mathematics colleague at DC who was also keen to explore Harkness), we returned to DC and started to practise Harkness learning and teaching with KS4 and KS5 students.

Mrs Lambert’s oracy journey began after a visit to Wellington College in the UK

Within a year we had six colleagues also adopting the approach and by 2019 we had 18 teachers in 12 subjects utilising Harkness to varying degrees. It was at this point that I was appointed Specialist Leader in Education: Innovative Pedagogy (a role that was subsequently refined to SLE: Oracy & Harkness) and I was very fortunate indeed to be sent by DC to Philips Exeter Academy (the birthplace of Harkness) for their intensive Exeter Humanities Institute. Concurrently, I was submitting my MSc dissertation, which has focused on the impact of Harkness lessons on students’ confidence – I had chosen to measure a non-academic outcome because oracy has as much of a social and emotional impact as it does academic; my research found that regular use of Harkness lessons increases students’ confidence.

Then COVID-19 hit… The shift to online and hybrid learning (social distancing regulations and classroom constraints meant that we had to rotate KS3 classes in and out of school in 2020-1), mask-wearing and solo tables in rows to adhere to social distancing rules meant that Harkness lessons were very hard to continue with, given that students could not sit around one table together, although a few of us did persevere online with some success.

Pictured: Year 7 students at Dubai College engaging on Oracy lessons. Every effort was made to continue Oracy classes at Dubai College, in some form, throughout the Covid 19 pandemic given its importance within the DC curriculum and positive impact on student learning.

Wave Two came into play. In September 2020, we decided to shift our focus to the younger students who had been most affected by the summer term online and the 2020-21 rotation in and out of school. We felt they were disconnected from one another, literally as well as figuratively, so we decided to channel our pedagogical focus on oracy, specifically the social and emotional aspect of it. Using ‘The Oracy Framework’ (created by Oracy Cambridge and the UK-based oracy education charity Voice 21), we looked at ways of using the Social & Emotional and Physical Strands to help students re-communicate with one another and to develop skills that we felt had declined (eye contact, gesture, listening to others).

To fully embed this focus, departments were asked to choose between Oracy and Metacognition as a focus for their practice and professional development. To support staff, we provided regular INSET sessions, working lunches (Pedagoos), Collaborative Learning Groups (CLGs) and CPD courses, alongside a central bank of resources and icons so that students and staff were all using a common language across subjects and stages. As a research-led school, we wanted to be sure that our oracy work was having an impact, so my NPQSL project focused on the physical skills of oracy in KS3, confirming that an explicit focus on key skills and regular use of oracy in lessons improved our students’ use of eye contact and gesture when talking in lessons.

Oracy Skills Framework, created by Oracy Cambridge and oracy education charity Voice 21

In parallel with our internal focus on oracy, I established the Dubai Oracy Hub as an online webinar series so that we could share ideas and best practice between teachers across the region – we had speakers from the UK as well as the UAE and a mixture of primary and secondary all share their fantastic work in empowering young people to learn to talk and also through talk; I’m hoping to organise our first in-person seminar in the Spring.

As well as establishing the hub as a means to provide free access to oracy CPD for teachers whose schools perhaps do not focus explicitly on it, I also started to be invited to deliver CPD at schools that were keen to embed an oracy focus too. Victory Heights Primary School were quick out of the blocks and I have worked with them for a few years now, supporting and championing the fantastic work that they have done; our Year 7 Learning Leaders (including Oracy leaders) facilitated a Year 6 inter-school competition last year, which Mike [Michael Lambert, Headmaster of Dubai College] and I were invited to judge. I have also delivered CPD to iPGCSE students at Birmingham University (Dubai), North London Collegiate School and Nord Anglia International School Dubai staff, the BSME Secondary English Network, as well as speaking at several conferences including METLC Online, ResearchED Dubai, the Speaking Citizens Conference: The Uses of Oracy, and I was deeply honoured to be invited by Professor Neil Mercer to co-present with him at the Global Schools Festival. At each of these events, I have shared our journey as well as practical ideas and tips in the hope that more children will have access to explicit oracy education. In this vein, I have been invited to join the Arcadia Development Board as an oracy and literacy advisor and am co-authoring a book chapter with Professor Arlene Holmes-Henderson about our oracy journey at Dubai College.

Victory Heights Primary School in Dubai is just one of the Dubai-based schools that has benefitted from the Oracy Hub Dubai set up by Mrs Lambert to facilitate the sharing of oracy ideas and pedagogy.

Back to Wave Two of our oracy journey…

The departments who chose to focus on oracy have now fully embedded oracy across year groups by mapping common tasks and assessments, using the framework to ensure that students cover all of the elements of each strand across their journey through that subject, from Year 7 to Year 13, where applicable.

Inaugurated in 2021, we have an annual Oracy Month at DC with weekly ‘Speakers’ Corner’ soap boxes and a school-wide oracy focus that culminates in a ‘No Pens Day’ and a KS3 oracy challenge; it’s a great time to see oracy flourishing across the site. Once masks and social distancing disappeared last year, we were able to bring together waves 1 and 2 with a re-launch of Harkness lessons across the school. We did this by supporting staff with an immersive three-day Harkness training course, which will run its third iteration this academic year; last year two BSAK teachers joined us to train and disseminate Harkness teaching at their school and we hope to invite more external practitioners to join us this year.

Philips Exeter Academy in the US is the birthplace of the Harkness method, which was established at the school in 1930 with the introduction of an oval table, around which students were invited to talk together. Over the past two years Dubai College has been sending staff to train in the Harkness method at the Academy.

As well as this, for the last two years we have sent two teachers to the Exeter Humanities Institute at Philips Exeter Academy (US) – this investment in staff training has paid dividends with these colleagues fully integrating Harkness into their departments as well as supporting other staff who want to develop their practice.

Three years of explicit oracy work with Key Stage 3 students have laid a strong foundation for Harkness lessons higher up the school; indeed we now have a number of teachers using Harkness with Years 7 and 8 and two departments have established Harkness-based units of work in Years 8 and 9. Alongside this, our RPEP (Rolling Positive Education Programme) not only includes specific sessions for Year 7 (Introduction to Oracy), Year 8 (Introduction to Harkness) and Year 9 (Public Speaking), but many of the other pastoral sessions have integrated oracy (talk tasks, pairs work, debates etc.) to teach and learn the content.

So developed is our oracy practice now, that we were visited by Beccy Earnshaw (CEO of Voice 21) and Professor Arlene Holmes-Henderson (Professor of Classics Education and Public Policy, MBE) in February in part for British Council funded research into oracy education overseas, but also to see how we have integrated and adapted Voice 21 resources (including the framework) and how we use Harkness lessons across the school.

The airy Jafar Centre at Dubai College was designed with oracy and the Science of Learning in mind

After three years of a single focus on one of our two learning and teaching foci (Metacognition evolved into the Science of Learning), this academic year we have asked staff to individually develop their practice with a stretch and challenge and SEND focus utilising oracy or the Science of Learning. It has been amazing to see the range of individual research projects that staff have embarked upon that utilise oracy, including Harkness lessons.

Our brand-new Jafar Centre was designed with oracy and the Science of Learning in mind and is home to beautiful new Harkness rooms, classrooms with modular seating and collaborative spaces where students can talk and learn together – a testament to just how central oracy now is to our school’s vision and very fabric. Staff are now regularly videoing Harkness and oracy lessons to share with colleagues and to use as a reflective tool to further develop their own skills.

How does Oracy work with the Harkness Model of teaching and Flipped Learning?

How does Oracy work with the Harkness Model of teaching and Flipped Learning?

![]() Harkness learning and teaching relies upon prior knowledge – students cannot sustain a critical discussion of a text, or explore lengthy problems, without knowing enough about the topic.

Harkness learning and teaching relies upon prior knowledge – students cannot sustain a critical discussion of a text, or explore lengthy problems, without knowing enough about the topic.

My Harkness lessons require students to prepare material in advance (for example, annotations of a text and/or the reading of secondary articles) so that they can then apply their knowledge to a question and build a deeper understanding of it collectively during our discussion.

Harkness lessons are just one form of oracy work, a scaled-up version of small group talk tasks. For an oracy task in a Year 7 lesson to be productive, students need prior knowledge – this could simply be previous lessons’ worth of instructional content that they then discuss and apply to a question, or reading completed for homework.

Flipped learning enables students to read material and acquire knowledge at their own pace, they can then apply this knowledge in the classroom and receive immediate feedback from their peers or teacher, as opposed to being sent home to complete 20 questions where they repeat an error and then must await feedback. Orally exploring and applying knowledge is an effective way for students to utilise prior learning and for teachers to assess understanding and feedback on the spot.

Pictured: student at Dubai College engaged in public speaking. It is a common misconception that oracy is the same as public speaking. While public speaking is one element of oracy, there is much more to Oracy, however, than public speaking alone.

Does Oracy help children to think better?

Does Oracy help children to think better?

![]() I encourage students to use ‘draft talk’, to orally discuss or explain their thinking with peers, to refine their thinking and argumentation, before committing their thoughts to paper. I have really noticed with the Sixth Form that regular Harkness lessons discussing a text, themes and/or essay questions, leads to better argumentation in essays and more creative thinking because not only do they develop a more robust thesis with integrated evidence because they have already discussed it collectively, but they are exposed to others’ thoughts and suggestions, making then think both critically and carefully about what to integrate into their own knowledge and understanding.

I encourage students to use ‘draft talk’, to orally discuss or explain their thinking with peers, to refine their thinking and argumentation, before committing their thoughts to paper. I have really noticed with the Sixth Form that regular Harkness lessons discussing a text, themes and/or essay questions, leads to better argumentation in essays and more creative thinking because not only do they develop a more robust thesis with integrated evidence because they have already discussed it collectively, but they are exposed to others’ thoughts and suggestions, making then think both critically and carefully about what to integrate into their own knowledge and understanding.

Listening carefully to others’ utterances forces students to think better too, they have to be engaged and focused – Harkness lessons are exhausting! – so that their responses build or challenge the thread of discussion, so they are constantly being critical and thoughtful in lessons.

How does Oracy help learning more widely?

How does Oracy help learning more widely?

![]() The moment a student has to explain their thinking, or explain a concept to a peer, they discover what they do or don’t know. Hearing others’ ideas, collaboratively sharing and co-constructing knowledge is powerful to behold and not only leads to deeper understanding, but it also teaches students tolerance and respect as they hear different perspectives on an issue, witness alternative approaches to a problem, or indeed hear different solutions to a question. Teachers can also identify misconceptions more readily in an oracy-driven classroom, they can also hear students’ logic and lines of reasoning, enabling them to challenge or praise thinking. Students also learn to listen – listening skills are key in oracy – and in this day and age it is perhaps as important to listen as it is to be heard.

The moment a student has to explain their thinking, or explain a concept to a peer, they discover what they do or don’t know. Hearing others’ ideas, collaboratively sharing and co-constructing knowledge is powerful to behold and not only leads to deeper understanding, but it also teaches students tolerance and respect as they hear different perspectives on an issue, witness alternative approaches to a problem, or indeed hear different solutions to a question. Teachers can also identify misconceptions more readily in an oracy-driven classroom, they can also hear students’ logic and lines of reasoning, enabling them to challenge or praise thinking. Students also learn to listen – listening skills are key in oracy – and in this day and age it is perhaps as important to listen as it is to be heard.

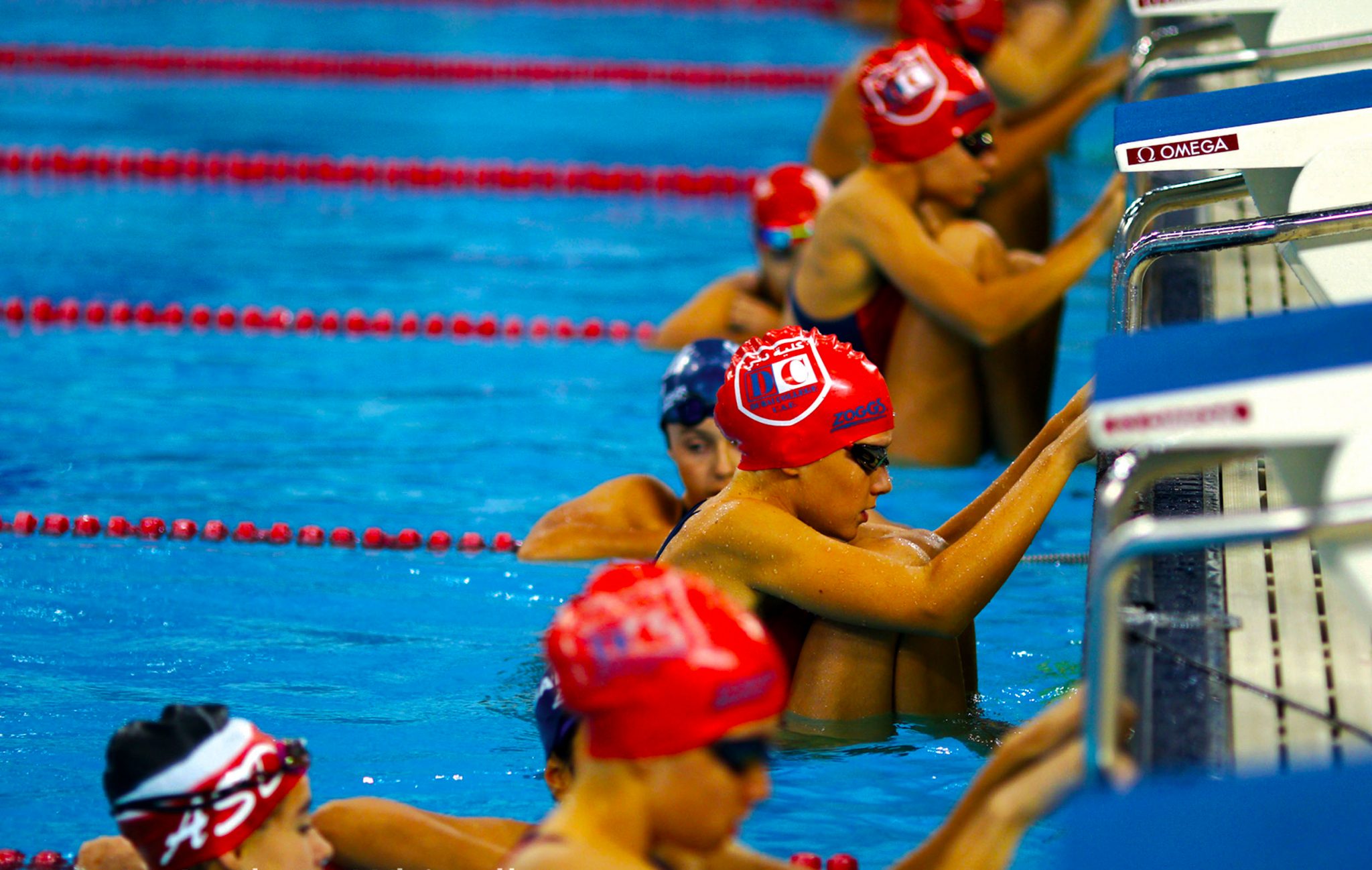

Whilst Dubai College is often viewed as just an academic school, we view academic achievement as just one of four pillars that support the school’s vision and ethos: Sport, Philanthropy and Creativity are equally important to us in developing caring, thoughtful and well-rounded young people who will be able to contribute to society in a meaningful way.

Oracy threads its way through all these domains, from team talks led by students on the pitches and courts, to collaborative discussions in Drama, Music and Art as students co-create pieces that reflect their voices and experiences, and to talking with Nepalese children, helping them to use their voices to learn and communicate at Jaisithok School and Shree Shree Jagadishwor Basic (Primary) School in Bimalnagar, which our community supports and visits.

We have over 160 ECAs at Dubai College (with more being added all the time), some of which are overtly oracy-based (for example, Junior and Senior Debating, Speechmaking Club, MUN, TedX Youth) but many incorporate an oracy focus to enable students to hear each other’s views as they work towards building or completing something or exploring a theory or concept: see an overview of Dubai College’s extracurricular activities here.

While Dubai College is often viewed as just an academic school, academic achievement is just one of four pillars that support the school’s vision and ethos: Sport, Philanthropy and Creativity are equally important.

Does Oracy help students navigate the Sciences as well as the Arts better?

Does Oracy help students navigate the Sciences as well as the Arts better?

![]() Oracy is often perceived to be easier to develop in the Arts and Humanities, which often have more discursive content that can be explored, or open tasks that lend themselves to debate and discussion, rather than discrete answers.

Oracy is often perceived to be easier to develop in the Arts and Humanities, which often have more discursive content that can be explored, or open tasks that lend themselves to debate and discussion, rather than discrete answers.

We have worked hard to develop oracy in the Sciences through group work, presentational talk and Harkness lessons – discussing and planning how to approach an experiment is a fantastic collaborative task before independently conducting it and then collectively discussing findings and analysing different results.

Our Mathematics department has embraced oracy across classes and key stages and their lessons in our new Jafar Centre are full of talk, wall work and co-construction of knowledge – they are so impressive to watch!

The key benefit that students are appreciating in the Sciences is hearing how others think and approach problems, which affirms understanding of a process as well as providing alternative perspectives, which are so important when developing knowledge.

What would a society look like if everyone was highly accomplished in the skills of Oracy?

What would a society look like if everyone was highly accomplished in the skills of Oracy?

![]() More tolerant! In an ideal world, people would listen openly to views antithetical to their own, collaborate effectively and productively with people very different to themselves, and agree to disagree with respect for others’ views. It would be a much more democratic and measured place to live – these are the skills we are trying to foster in our students through oracy work and Harkness lessons.

More tolerant! In an ideal world, people would listen openly to views antithetical to their own, collaborate effectively and productively with people very different to themselves, and agree to disagree with respect for others’ views. It would be a much more democratic and measured place to live – these are the skills we are trying to foster in our students through oracy work and Harkness lessons.

Is Oracy fundamental to creating/imagining a truly democratic society?

Is Oracy fundamental to creating/imagining a truly democratic society?

![]() Yes! In its truest meaning, rule of the people by the people would entail everyone’s voice being heard. Practically, we know this is impossible and often the loudest voices dominate and drown out those less articulate, less motivated or less privileged.

Yes! In its truest meaning, rule of the people by the people would entail everyone’s voice being heard. Practically, we know this is impossible and often the loudest voices dominate and drown out those less articulate, less motivated or less privileged.

In our region, it is sometimes a gender imbalance that prevails too, so empowering young women to voice their opinions and be heard is a key part of our role as educators.

When I discuss influential orators with Year 7, it is great to hear that they look up to Malala Yousafzai and Greta Thunberg, appreciating that oracy is not so much about learning to talk ‘properly’, but that it is more about articulating one’s thoughts and being heard – communicating big ideas in a way that others listen to them and take notice.

Oracy helps inspire young women to be spokespeople such as Greta Thunberg

What are the practical advantages, as a life skill, in becoming gifted in Oracy?

What are the practical advantages, as a life skill, in becoming gifted in Oracy?

![]() When students and parents see our Harkness tables, they immediately make the visual leap to a boardroom scenario, seeing the application of skills very clearly into the professional sphere. Developing strong oracy skills will equip a young person to be confident to express themselves in a range of scenarios. They will understand context, how to speak in different scenarios, how to engage their audience, but crucially how to converse with others, not to simply talk at them. This will make them positive and tolerant contributors to society, a life skill that will benefit all they interact with.

When students and parents see our Harkness tables, they immediately make the visual leap to a boardroom scenario, seeing the application of skills very clearly into the professional sphere. Developing strong oracy skills will equip a young person to be confident to express themselves in a range of scenarios. They will understand context, how to speak in different scenarios, how to engage their audience, but crucially how to converse with others, not to simply talk at them. This will make them positive and tolerant contributors to society, a life skill that will benefit all they interact with.

We should also see oracy as a key skill in an increasingly digital world. The OECD’s position paper, The Future of Education and Skills Education 2030 (2018) suggests that ‘students will need to apply their knowledge in unknown and evolving circumstances. For this, they will need a broad range of skills, including cognitive and meta-cognitive skills (e.g. critical thinking, creative thinking, learning to learn and self-regulation); social and emotional skills (e.g. empathy, self-efficacy and collaboration); and practical and physical skills (e.g. using new information and communication technology devices)’ (p.4).

Are there disadvantages in becoming gifted in Oracy?

Are there disadvantages in becoming gifted in Oracy?

![]() I suppose one disadvantage to being gifted in oracy is that others will come to rely upon your voice, to expect you to lead a discussion or to speak for them. This can of course be a burden and we do see some students take on this mantle only to find it exhausting to always be expected to dominate.

I suppose one disadvantage to being gifted in oracy is that others will come to rely upon your voice, to expect you to lead a discussion or to speak for them. This can of course be a burden and we do see some students take on this mantle only to find it exhausting to always be expected to dominate.

Having a dominant voice often brings influence too and it’s a fine line for young people to traverse because everything they say can have influential weight and the expectation for a teenager to always say the ‘right’ thing is unrealistic.

What I hope we are fostering at DC is an environment where students take risks and sometimes get things wrong – saying the ‘wrong’ thing – but that they have the confidence to not only speak in the first place, but that their peers feel able to challenge them respectfully and support one another as they navigate a path that represents their collective voices.

Is Oracy a dangerous gift in the wrong hands?

Is Oracy a dangerous gift in the wrong hands?

![]() I think I’ve touched on this in my previous answer, but history provides us with many examples of persuasive orators who have had negative influences on communities, rallying masses to a cause with devastating effects. The ability to speak well is a form of power that needs to be handled carefully and used for good – arguably too many politicians take advantage of their oral prowess and sway their followers to their own self-interested views.

I think I’ve touched on this in my previous answer, but history provides us with many examples of persuasive orators who have had negative influences on communities, rallying masses to a cause with devastating effects. The ability to speak well is a form of power that needs to be handled carefully and used for good – arguably too many politicians take advantage of their oral prowess and sway their followers to their own self-interested views.

I enjoy teaching Julius Caesar for this exact reason – Brutus and Mark Antony in Act 3 demonstrate just how fickle the masses are and how clever rhetoric, the ability to articulate views logically and manipulate others’ emotions can turn a crowd quickly. Students quickly spot the modern parallels with social media influencers and youtubers who can sway naïve viewers through talking with conviction. Teaching oracy at school hopefully equips young people with the ability listen critically, to question what they hear and to spot crafty rhetoric that is trying to influence them.

Learning more about oracy can help students to be more critical listeners in every part of their lives, including the online world. It can help impressionable teens to spot and question verbal techniques used by YouTubers and other influencers.

Does being accomplished in Oracy mean that you think more rationally? Less emotionally? Does it make people more similar, or enable people to express their differences better?

Does being accomplished in Oracy mean that you think more rationally? Less emotionally? Does it make people more similar, or enable people to express their differences better?

![]() Similar to writing, we all express ourselves uniquely and individually when we speak and I think that it is important to celebrate diversity, our dialects, idiolects and accents when teaching oracy. Similarity comes from a shared language and understanding that is fostered by studying how to express ideas effectively and to an extent we do teach sentence stems in KS3 that foster the four key oracy contributions (build, link, question and challenge) so that students have the tools to express their differences better.

Similar to writing, we all express ourselves uniquely and individually when we speak and I think that it is important to celebrate diversity, our dialects, idiolects and accents when teaching oracy. Similarity comes from a shared language and understanding that is fostered by studying how to express ideas effectively and to an extent we do teach sentence stems in KS3 that foster the four key oracy contributions (build, link, question and challenge) so that students have the tools to express their differences better.

Does oracy make us more rational? Perhaps, it encourages logical expression of ideas and critical thinking, but if you watch a student-led Harkness lesson in full flow it is far from unemotional! Students express themselves with passion and defend their ideas vehemently – expressing your ideas well and effectively requires an emotion to be engaging and convincing.

Can you provide me with a real-world example of the transformation of a child you have seen take place after they have been introduced to the skills of Oracy?

Can you provide me with a real-world example of the transformation of a child you have seen take place after they have been introduced to the skills of Oracy?

![]() When I fully committed to teaching A Level Literature via Harkness lessons, I picked up a Year 13 class with a student who was described by their Year 12 teacher as ‘silent, does not contribute, lacks confidence’. I taught this class three times a week, all our lessons were timetabled into our bespoke Harkness room and step by step I coached and cajoled them into adopting Harkness philosophically, as well as practically, as our means to learn.

When I fully committed to teaching A Level Literature via Harkness lessons, I picked up a Year 13 class with a student who was described by their Year 12 teacher as ‘silent, does not contribute, lacks confidence’. I taught this class three times a week, all our lessons were timetabled into our bespoke Harkness room and step by step I coached and cajoled them into adopting Harkness philosophically, as well as practically, as our means to learn.

Step by step I weaned them off me as ‘sage on the stage’ and adopted an approach of partnership whereby I was either but one voice within their collective enterprise, or wholly removed, observing from off the oval table.

As I was conducting my MSc research using this class as the focus group, I decided to focus on the data of my silent student, tracking their progress across the year. I looked at their initial and final self-reported attitudes towards talk, learning and confidence; I tracked their contributions to discussions numerically and by length of utterance; and at the end of the year, I interviewed them.

My lesson observations recorded a blossoming of confidence as this young adult gradually found their voice, literally and metaphorically, they began to talk – at first just once or twice in a lesson, then incrementally more. With every lesson their confidence grew as they began to see and hear that their views were well received, that they were praised by their peers and me for perceptive points.

They transformed over the space of six months into a key contributor in the group. When I interviewed them for my final data capture, they, and I, cried as they acknowledged that they had changed beyond recognition. They said that they loved coming to lessons, that they enjoyed discussing literature with their peers publicly and that they liked who they had become. Such a transformation is not quantifiable, albeit my qualitative data evidenced their change, but for me it was one of the most powerful moments in my teaching career and confirmed to me that oracy can be transformative and Harkness lessons powerfully beneficial.

The Labour Party in the UK are seeking to transform education by introducing Oracy into the curriculum.

The Labour Party in the UK is seeking to transform education by introducing Oracy into the curriculum. They hope it will have an impact in schools where the learning environment, in some/many cases, is not conducive to learning and investment has been cut badly for decades. Can Oracy make a difference? What advice would you give the Labour Government? What advice would you give teachers in the UK wondering whether it will make a difference? Would this be a transformation tool for teachers struggling in the developing world with a lack of resources?

The Labour Party in the UK is seeking to transform education by introducing Oracy into the curriculum. They hope it will have an impact in schools where the learning environment, in some/many cases, is not conducive to learning and investment has been cut badly for decades. Can Oracy make a difference? What advice would you give the Labour Government? What advice would you give teachers in the UK wondering whether it will make a difference? Would this be a transformation tool for teachers struggling in the developing world with a lack of resources?

![]() The drive for a greater focus on oracy has long been championed by Voice 21, Professor Neil Mercer and Professor Robin Alexander, Emma Hardy MP, and the Oracy APPG who have been calling for educational change for a while. It’s fantastic that the Labour Party are seeking to bring back a more explicit focus on oracy and to make it part of every child’s education, rather than it depending upon the school you attend.

The drive for a greater focus on oracy has long been championed by Voice 21, Professor Neil Mercer and Professor Robin Alexander, Emma Hardy MP, and the Oracy APPG who have been calling for educational change for a while. It’s fantastic that the Labour Party are seeking to bring back a more explicit focus on oracy and to make it part of every child’s education, rather than it depending upon the school you attend.

The key thing about oracy is that it is does not require expensive resources, at its simplest it does not require paper or pens or textbooks, it just requires time and a focus. There are amazing oracy projects running across the globe because oracy does make a difference – it equips young people with the ability to express themselves, to listen, and to feel heard, which are key to combatting disillusionment in educational and social settings.

I certainly don’t feel equipped to advise the Labour Party – they’re receiving much better advice from the experts! – but prioritising the spoken word to learn, teach and assess knowledge is key, particularly with AI advancing at pace and calling into question the integrity of students’ writing.

Hearing a student discuss a text or mathematics solution provides quick insight into whether they know what they are talking about, and what they think.

If you wanted to try and relay to a fellow teacher who is struggling to make an impact in their school, the gift of Oracy, and provide them with a toolbox to make it work quickly and simply, and you had barely three minutes in an elevator stuck between floors to convey what they can do, and how important it is, what would you say to them?

If you wanted to try and relay to a fellow teacher who is struggling to make an impact in their school, the gift of Oracy, and provide them with a toolbox to make it work quickly and simply, and you had barely three minutes in an elevator stuck between floors to convey what they can do, and how important it is, what would you say to them?

![]() Start with The Oracy Skills Framework and Glossary – identify which aspects of oracy are already working well and which areas need focused work. Diagnosing and targeting a specific area to develop will make it easy to start to see progress. Focus on just one year group, even one class, and remember that just as reading and writing are skills that develop through practice, so too does oracy. There won’t be an overnight impact, although addressing the physical strand can have rapid results, it will be gradual and incremental because it will be embedded and refined through students doing it over and over again, just like they do with their writing or numeracy. Start with Voice 21’s website and resources, follow them on X.

Start with The Oracy Skills Framework and Glossary – identify which aspects of oracy are already working well and which areas need focused work. Diagnosing and targeting a specific area to develop will make it easy to start to see progress. Focus on just one year group, even one class, and remember that just as reading and writing are skills that develop through practice, so too does oracy. There won’t be an overnight impact, although addressing the physical strand can have rapid results, it will be gradual and incremental because it will be embedded and refined through students doing it over and over again, just like they do with their writing or numeracy. Start with Voice 21’s website and resources, follow them on X.

I would then read Gaunt & Stott’s book Transform Learning and Teaching Through Talk: The Oracy Imperative (2019) if a Primary/KS3 oracy focus is the aim, or The Best Class You Never Taught: How Spider Web Discussion Can Turn Students into Learning Leaders (Wiggins, 2017) or A Classroom Revolution: Reflections on Harkness Learning and Teaching (Cadwell & Quinn, 2015) if Harkness lessons for older students is of interest. All three books were instrumental to my early steps in developing Oracy and Harkness at DC. For the research-focused teacher, I highly recommend Rupert Knight’s Classroom Talk: Evidence-based Teaching for Enquiring Teachers (2020) as a compact overview of oracy research.

Further information

Learn more about Dubai College here.

Read our review of Dubai College here.

OECD (2018). The Future of Education and Skills Education 2030 – Position Paper.

Voice 21 & Oracy Cambridge. (2019). The Oracy Skills Framework and Glossary.

Britton, J. (1983). Writing and the story of the world. In B. Kroll & E. Wells (Eds.), Explorations in the development of writing, theory, research, and practice (pp. 3–30). New York: Wiley. Available here.

Cadwell, J. S. & Quinn, J. (Eds.). (2015). A Classroom Revolution: Reflections of Harkness Learning and Teaching. Exeter: Phillips Exeter Academy. Available here.

Gaunt, A. & Stott, A. (2019). Transforming Teaching and Learning Through Talk: The Oracy Imperative. London: Rowman & Littlefield. Available here.

Knight, R. (2020). Classroom Talk: Evidence-based Teaching for Enquiring Teachers. St Albans: Critical Publishing. Available here.

© SchoolsCompared.com 2024 – 2025. All rights of Sarah Lambert reserved. Extended parts of this article should not be shared without permission.

Leave a Response