Using PISA to Benchmark UAE Schools – Why, & Why Not…

Many parents will have come across discussion of something called PISA. Schools are being helped by the Schools Inspectorates across all 7 Emirates to improve their education of our children – and PISA is one way they are being measured.

In the following we look at what PISA is – and ask what it tells us about the state of education in the UAE. Can it help parents choose the best school? Is it going to drive up standards? Is it in any way useful for parents or is it really something complicated whose real value lies only behind the scenes? And does it give us as parents any better of understanding how the education our children are getting here, compares with that they would receive in other countries?

What is PISA and why is it important for parents?

What no one should be in doubt of is that the current system of education in the UAE, looked at as a whole, is not at the standards the nation expects or aspires to. This is recognised at the highest level:

“The UAE Vision 2021 National Agenda emphasizes the development of a first-rate education system. This will require a complete transformation of the current education system and teaching methods.” Vision 2021. UAE Government.

PISA is one tool the UAE government is using to put things right. Arguably it is the single most important tool the government has to understand how well our children are being educated in the UAE because it provides a simple way of comparing performance of our children here, with those in other countries.

The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) is a set of standardised tests designed and delivered by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to measure student’s performance at the age of 15.

Currently 72 countries take part in the tests every three years, including all 7 Emirates of the UAE.

PISA focuses in 4 areas in each child’s education: Mathematics; Science; reading/linguistic understanding; and “problem solving” (introduced in 2003).

In each three yearly cycle, one of these four areas is emphasised and the results more heavily analysed and benchmarked. Most analysis concentrates on the three traditional areas of reading, Mathematics and Science.

PISA is important because it is designed to provide a neutral, universal, unarguable and fair way of measuring how well children are being educated in any country that sits the tests. Whether it actually does this is another matter which we cover below. Not everyone is in agreement.

It is worth noting for completeness that there are two leading alternatives whose areas PISA effectively combines together – and both of these too the UAE is using as part of its to drive to drive up standards for all our children:

- the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study(TIMSS) [ started in 1995]; and,

- the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) [started in 2001] by the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement

What all these studies are attempting to do is give children in the UAE exactly the same test that is sat in all the countries taking part – to then enable the UAE government and individual rulers to use the results to measure how well our schools are doing compared with the rest of the world – and with this information to understand how to improve our schools for children.

Because children are sitting exactly the same test, the results are, as a result, supposedly, comparable. In theory, governments can say, for example, that children in their country are being educated better – and extrapolate from this that individual curriculums, whether IB, A Level or US systems for example, are better than the alternatives.

Some argue that parents can, and should, use the results to choose whether to send their children to, for example, UK schools – or, say, Canadian ones (which incidentally perform better in PISA scoring), solely on the basis that a given curriculum performs better under PISA.

Does anyone really listen to PISA results?

Yes. The results are taken seriously. They have been used to work out which curriculum educates children best – and which educational systems work to deliver the highest level of education in the core areas of Science, Mathematics and Reading/linguistic understanding. For example, in the USA, concerns about PISA performance were instrumental in leading to the development of national Common Core Standards.

Logically, assuming (1) the test is fit for purpose; (2) it is interpreted accurately; and (3) that testing of children in this universal way actually works – all big ifs – it would seem to be a good way of assessing how good different curricular and education system are in practice in ensuring children meet required standards of education.

There is one other benefit of PISA: timing. Because PISA targets students aged between 15 years 3 months and 16 years 2 months at the time of the assessment, it is well placed to understand how the educational system has performed at the point at which in many countries compulsory schooling ends (although increasingly we are now seeing market pressures push children to stay at school until 18 and these are likely to strengthen). PISA measures children at, so it is argued, an ideal reference point to determine the real outputs of an education system and its effectiveness when it matters (or too late for those children tested depending on how you look at it).

So, on paper at least, PISA is the single, one-stop, complete solution to deciding for parents in the UAE which curriculum school to choose to get the best education. It should provide parents at a glance an answer to the question of whether the UAE is a good place to educate children and whether, for example if practicable, children should be educated offshore.

If life were that simple…

How does PISA choose a fair sample of students – and not just the best?

In each participating country or economy, a sample of between 4,500 and 10,000 students are chosen from at least 150 schools through a statistical framework which ensures that they (supposedly) represent all students aged 15 in the country. From this sample, results are weighted and analysed to determine the characteristics of the entire student population. The sample includes students in public and private school who are enrolled in either general or vocational education.

It is worth noting that in the UAE schools are not included that do not teach with English or Arabic as a first language. This includes a number of language/cultural schools.

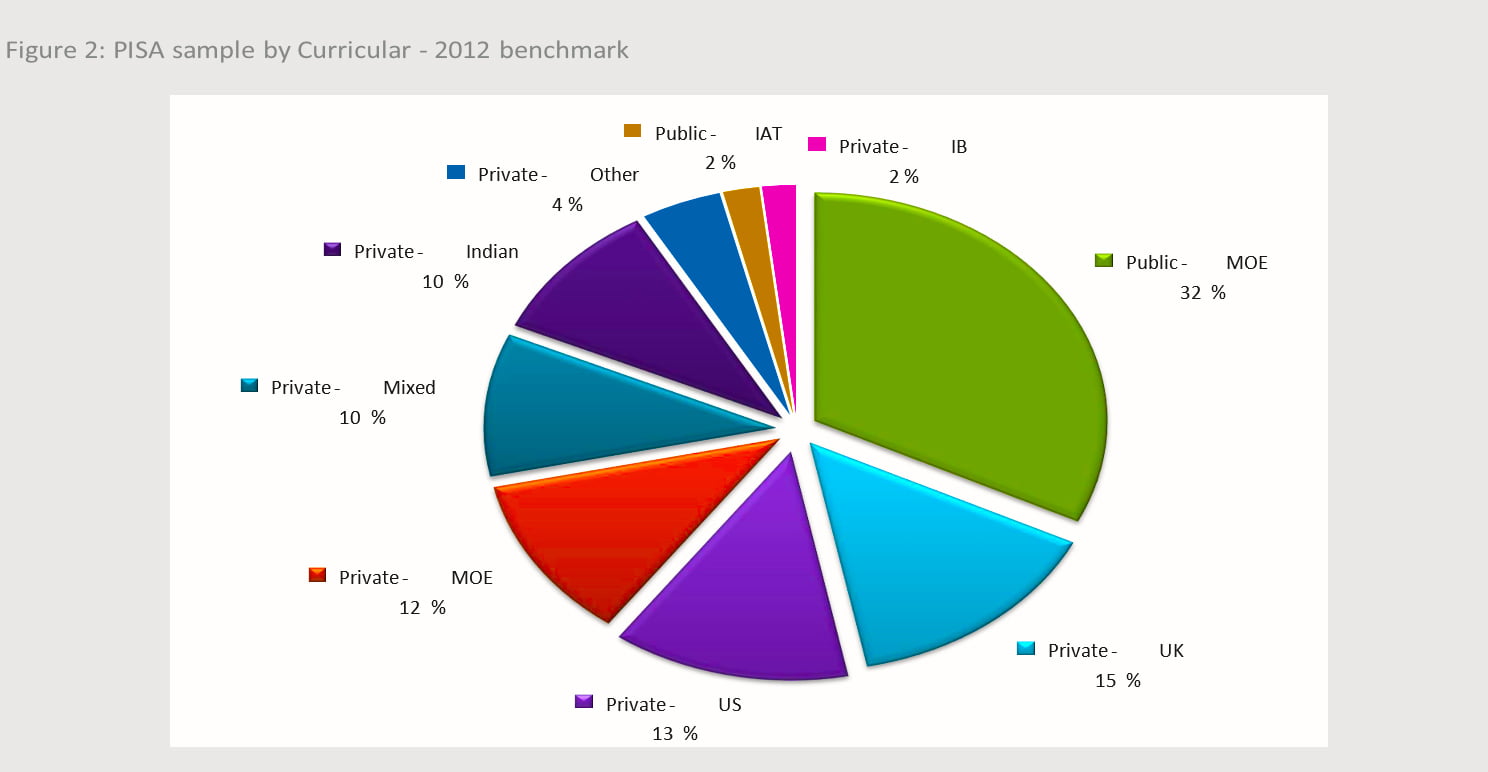

Schools are included which offer at least 13 different curriculums, including IB, UK, Indian, US and Arabic schools.

Why is PISA so important for the government of the UAE?

“We are at the start of the road… to our vision… for every peak we reach overlooks the next. Only those who thrive to achieve are on top…” His Highness Sheikh Mohammed Bin Rashid Al Maktoum

What is not in doubt, when looking at PISA, is the impressive, genuine and serious commitment of the Dubai government to significantly improve the education system for all children in the Emirates.

Arguably this started with the establishment of the Inspectorates in Dubai and Abu Dhabi – and via the MoE for other emirates.

Practically, as part of this drive, we have seen school closures, including of the villa schools – and arguably, most effective of all, the open publication – in Dubai and Abu Dhabi – of inspections, production by the Inspectorates of very detailed improvement plans for individual schools and teacher training.

All of this is now being provided to schools so that they know exactly what they need to do to meet the minimum “Good” standard of education required. There is no reason any longer for any school not to be performing at this minimum “Good” standard, as identified in every school’s inspection. There are, however, still too many schools performing below this standard.

One thing, however, Inspections cannot do, is make sense of the complexity that comes from having so many different curricular.

The UAE, in the sheer scale of choice of schools, brings the whole educational world into a single place. Inspections can only really judge the effectiveness of schools, at least in terms of curricula, within their own terms. There are more than 30 different curricula operating currently within UAE schools.

Given this complexity, PISA provides the government with a critical tool for seeing very quickly how the UAE is performing across most school types – and measuring the performance of schools over each 3-year period between PISA testing.

“Large scale standardised international assessments such as PISA, allow both comparison within a country despite differences in school curricula, as well as between countries internationally.” UAE Ministry of Education

PISA History in the UAE

The UAE first participated in PISA through Dubai’s involvement in PISA 2009, followed by the remaining Emirates in 2010 as part of a special round known as PISA 2009+.

The UAE education system as a whole is currently achieving well below the OECD average for its children.

In response, the UAE governments have set very high PISA targets as part of their UAE Vision 2021 goals. The aim is to rank in the top 20 of all countries in the world by 2021.

To put context to the ambition at play here, achieving this will put the UAE educational system at a level well above countries including the US and UK.

This will require US and UK schools in the Emirates, for example, to punch well above their home-grown average PISA scoring for the same curricular. It will require the UAE, currently 48th in the world, to rank above the UK (27th), France (26th) and the US (40th) in Mathematics, above the UK (22nd), US (24th), China (27th) and Switzerland (28th) in reading (the UAE is currently in 47th place) – and in Science the story is similar – the UAE would need to rise 26 places from its current 46th position in the world, overtaking the US, France and Russia in the process.

To achieve this it is likely that the UAE would need to have brought a significant majority of UAE schools up to a Good standard or higher and have effectively removed the very weakest schools from the system entirely.

Why is the UAE set on this?

For the UAE, the argument is that by boosting the average PISA scores of 15 year olds it will increase the country’s GDP by more than 100 trillion US$ over the lifetime of school leavers because they will be able to work more productively for the economy and innovate. This is more revenue (by a long way) than the UAE can extract from all its natural resources combined.

For individual children, it is about improving their life chances.

The OECD argues that its tests measure the skills needed to create wealth. By implication the OECD is claiming that schools whose children do well under PISA will be those who have successful careers and generate wealth. This is, it is argued, why as parents we should care about PISA. If we choose a school with a curriculum that scores well under PISA, we are choosing a school that should improve the life chances for our children. If an educational system scores highly under PISA as a whole, it is likely that our children will graduate into a country with a highly successful economy delivering jobs and prospects for our young men and women as they graduate looking for employment or seeking to start their own businesses – or be in high demand in any economy in the world.

The implication is that all curriculums, whether British, Indian, IB, US or any other, should be continuously re-drafted and re-designed to fit better with PISA.

How are UAE schools actually performing in PISA global rankings?

In the following we look at the first three years of PISA testing.

2009 – Core focus Reading

This is when the Emirates joined PISA and started measuring how the educational system is really performing for our children.

Dubai joined in 2009 with the rest of the Emirates joining in 2010. Dubai’s data was merged with that of the other Emirates and was then, as now, reported as a single entity: the United Arab Emirates.

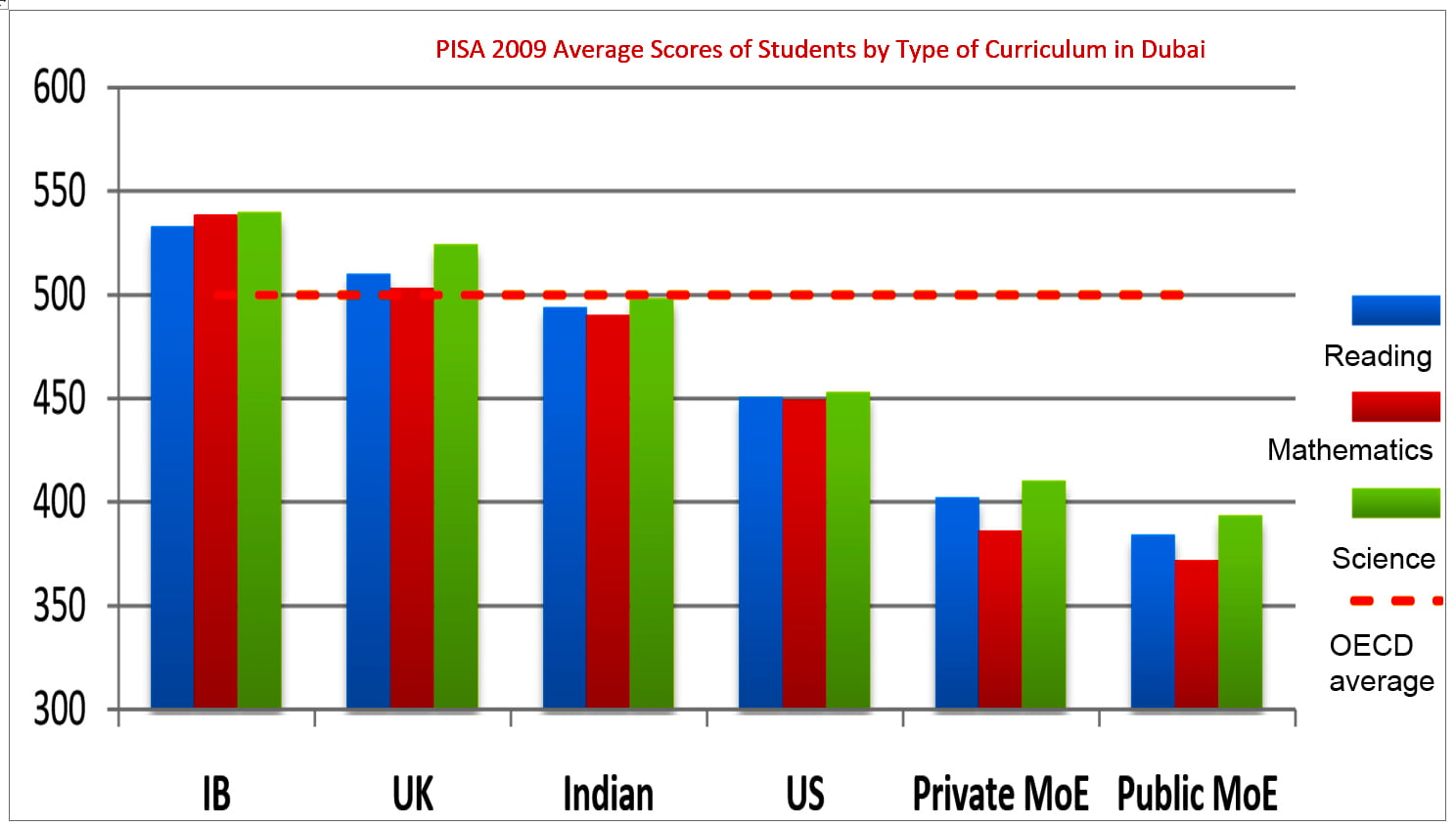

Dubai scored as follows. On first looks, the numbers are fairly meaningless – but we will try and bring them to life. Bottom line – the scoring is not good – especially when you consider the number of ‘Very Good’ and ‘Outstanding’ rated schools (by global standards) we do have in the Emirates.

We have shown scoring in the three core areas:

Reading: The UAE as a whole scored 431. Putting this in context, Shanghai scored top with 556. The OECD average was 493 which statistically included a range of countries including the United States, Sweden, Germany, Ireland, France and the United Kingdom.

Mathematics: The UAE as a whole scored 421. Again, putting this in context, Shanghai scored top with 600. The OECD average in this area was 496 which statistically included a range of countries including the United States, France and the United Kingdom.

Science: The UAE as a whole scored 438. Shanghai again topped the rankings with 575. The OECD average was 501 which statistically included the United States, Norway, Denmark and France (the UK and Germany scored more highly than the average in Science with scores ranging between 514 and 520)

So how, given our many excellent schools, did Dubai fair so badly? Pulling down Dubai’s results is the inclusion of UAE public schools – but also a number of private schools that are failing children. It is not exclusively a public schooling problem, but public schools are of significant concern. It is worth noting that around half of sampled children sampled were Emirati – more on this later. Emirati parents should be aware, however, that many argue that the tests, in the way they are written, discriminate against the culture of our local parents – and this should be weighed in the balance.

The key lesson, however, for parents from these first results – and in those that follow, may be what they tell us about the curricular that, at least for the OECD, are likely to produce the best educated children (understood by the OECD in a very restricted way as those that will be most highly paid and productive in their later careers.)

Sadly, the data that has been release is still quite limited. However, it is clear that for parents seeking to maximise the chances for achieving the kinds of success the OECD considers important, parents should be looking at IB schools first, followed very closely by British schools.

IB and British schools stand out in terms of performance – with all children, for example, meeting or exceeding Dubai average performance.

US schools fall significantly behind and significant numbers of children in both Indian and US schools to not achieve even Dubai average levels, for example, in even basic reading.

We have no further breakdown, beyond the above table table released by the KHDA, of the performance of the other curricular schools standing within the total 13 curricular involved in testing in 2009 or in later years.

2009: PISA bottom line?

The key facts we learned in 2009 are that

- around 4 in10 UAE students do not have a proficiency in reading literacy that the OECD believes is necessary for them “to participate effectively and productively in life.”

- This figure worsens to around half of all children in the UAE are not achieving the expected standards in Mathematics.

- Around 4 in 10 children in the UAE are not meeting the required minimum functional standards suggested in Science.

Taken as a whole, the UAE is scoring around 25% worse than the average of PISA participants.

It is also worth noting that across the board boys are achieving statistically worse than girls – and that in Science the gender gap in the UAE was the largest of any participating country.

Finally, to maximise the chances of getting a PISA defined good education, as parents, we should be looking at British or IB schools. If local families can afford it, it is advisable too, to source a private rather than public school education.

2012 – Core focus Mathematics

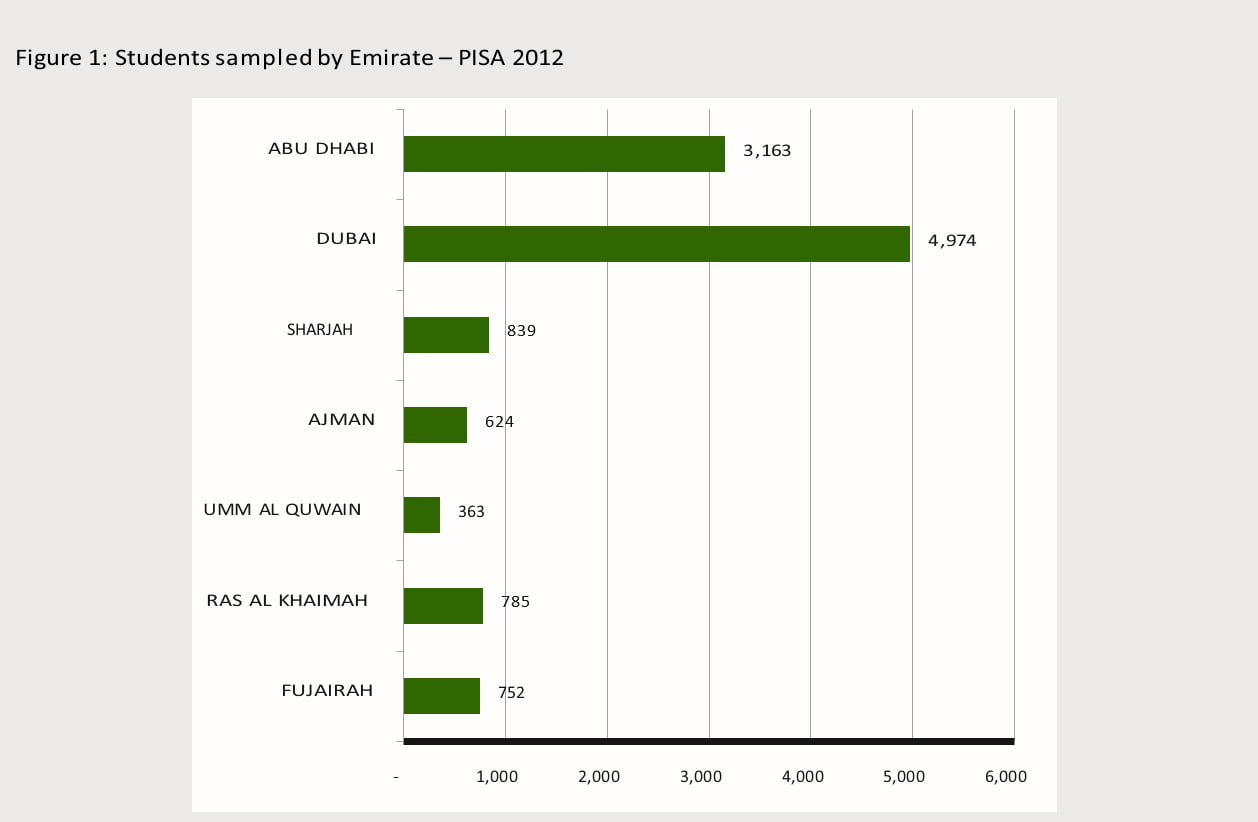

In 2012 a total of 11,500 15-year old students from 375 schools across all 7 Emirates of the UAE took part in PISA testing.

It is also worth noting the spread of curricular schools included:

The result showed very significant improvement in the UAE over the 3 years since the UAE first took part in PISA. Scores rose by between 10 and 13 points in each of the three core areas:

Reading: 442 (Rising from 431 in 2009)

Mathematics: 435 (Rising from 421 in 2009)

Science 449 Rising from 438 in 2009)

This level of improvement was seen as exceptional amongst all other countries in the world taking part.

However, this level of scoring still falls a long way short of the basic minimum education considered necessary for children to succeed.

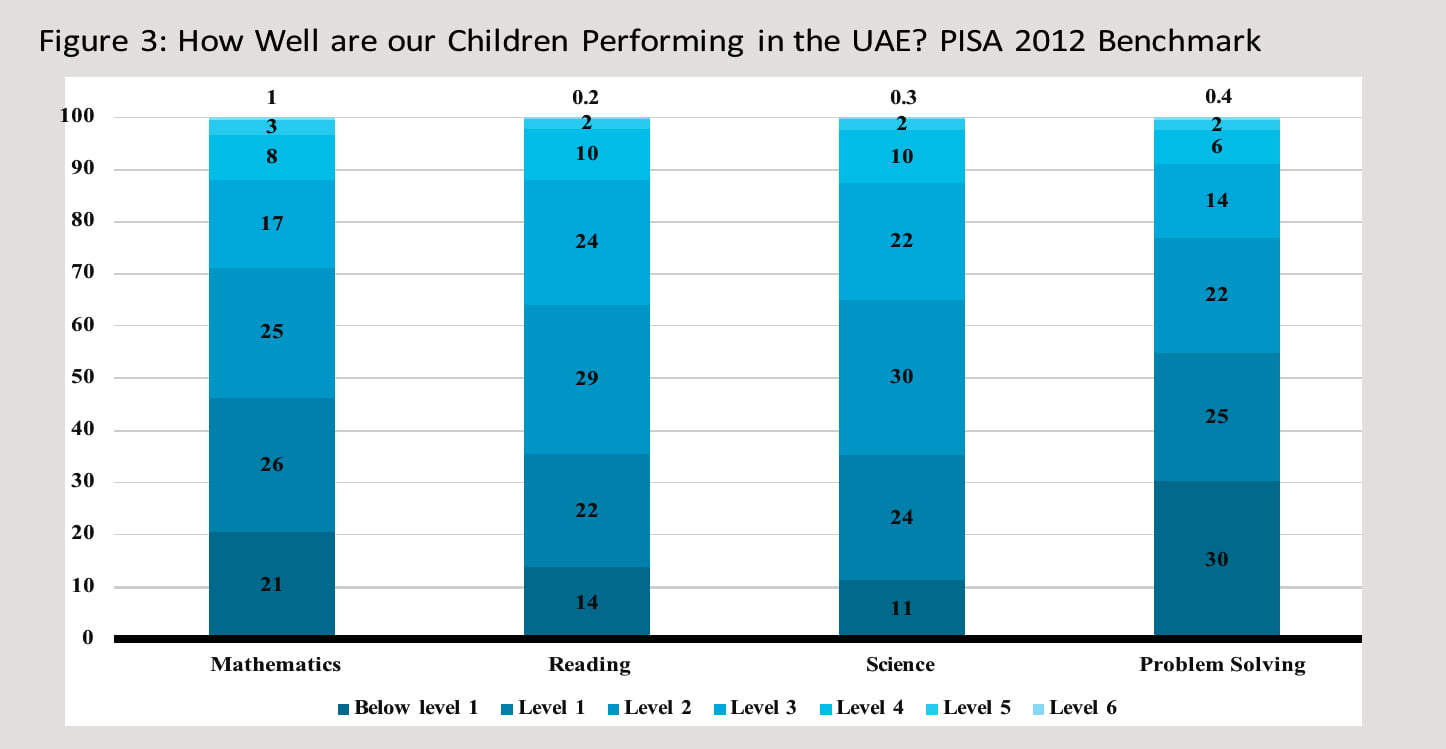

Bottom line is that that in 2012 the UAE continued to perform way below expectations despite the improvement it achieved since its first PISA in 2009:

- More than 6 children in 10 still did not meet the standards of reading (64%), and 7/10 students in problem solving (77%), deemed necessary to be successful;

- Over one third of all students were found to be achieving below the Level 2 “failing” proficiency threshold in reading and Science; and,

- This rose to half of all students in the UAE failing proficiency in Mathematics and Problem Solving.

Positively, whilst frustratingly the figures are not broken down, between 2% and 3% of students are operating across the board with skill levels that compete with the best in the world – and it is probably fair to assume that the majority of these are drawn from IB and UK private schools in the UAE.

2015 – Core focus Science

In 2015, the last time PISA was sat in the UAE, 6,798 students from Dubai schools were sampled, a 36.7% increase in the sample from 2012. This scoring is the last we have before publication of the next round of tests due in 2018. There will only be two more PISA tests test by 2021 so the UAE has in theory not much more than 4 years left to achieve its ambition of scoring in the top 20 countries for PISA in the world.

To understand just how ambitious this is, in 2015 the UAE didn’t get higher than 46th in the world:

- In Mathematics the UAE ranked 47th of participating countries (rising from 47th)

- In Science the UAE ranked 46th of participating countries (dropping from 44th)

- In reading the UAE ranked 48th of participating countries (dropping from 46th)

Given the improvements of 2012, 2015 results were disappointing.

The OECD average in 2015 was 493 in science, 493 in reading, and 490 in mathematics.

The UAE score for Science was 437, down 12 points from 2012 results; the mean score for Mathematics was 427, down seven points; whilst the mean score for reading was 434, down eight points from the previous round of tests.

Whilst the UAE moved up one place in Mathematics, it fell two places in both Science and reading.

Bottom line? The education system in the Emirates continued to perform significantly below average in all three areas:

“PISA scores for the UAE are way below for where you would predict them to be given the wealth of the country and the investment in education, maybe even the quality of the teaching force. So there’s a big gap between what you would expect and what you get.” Andreas Schleicher, Director, Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

From the information we have, private schools in Dubai from across all curricular, scored at or above the average in Science (497) and reading (493).

However, in Mathematics, whilst our children’s scores improved by three points to 484, they still remain, even in the private sector, under the OECD average.

UAE pupils as a whole, including public schools, continue to fall below the OECD average in all subjects.

1 in 5 of all 15 year olds in the UAE do not reach, for PISA, a level that everyone should achieve before leaving school.

Whilst we do not have access to the raw data, we feel it is safe to assume that UK and IB schools continue to perform very highly. We do know that 1 in 10 students in the UAE, for example, performed at the highest level in Science in 2015.

Why are our schools not achieving to standards we want?

There are many possible reasons.

One key issue identified by the OECD is the way our schools focus on children reproducing knowledge:

“Students in the UAE are very good in reproducing subject matter content but are very bad at extrapolating from what they know, using and applying their knowledge in a novel situation. That’s really what the PISA test is about; it explains the [UAE’s] performance.” Andreas Schleicher, director at Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

Research too has shown that a “big hindrance” for Arab pupils sitting for the Pisa is our pupils’ ability to read at the speed required to answer the question in time.

So should we value PISA?

This is difficult. Proponents say that PISA testing gives countries, and parents, the most credible, and trusted of any educational league tables.

They argue that only universal testing like PISA can assess performance across different curricula and countries.

They argue that they are now relied on by governments as a measure of how well their educational systems are performing and influence policy developments in education worldwide.

However, not everyone agrees.

Sir Anthony Seldon, former Head of both Wellington and Brighton Colleges, criticises league tables as “arguably doing more harm than good because they are skewing schools and national education systems away from real learning towards repetitive rote learning.”

To evidence this critics point to the fact that 13% of the world’s top performing PISA students have come from just 4 provinces in China.

Their attainment is running at the equivalent of around three years of normal schooling, a degree of education that is losing any chance of children experiencing a childhood, or understanding the world in any form of ‘lived” context outside books.

Many argue that, in China, “tiger” parents and the government are creating a pressure cooker system of examinations to meet PISA attainment as an end in itself. Nearly all of the sampled families in China used private tutors, distorting the base results of what schools themselves were achieving.

They also ask whether the OECD should be dictating how and what children should learn – the OECD completely disregards culture – and, it is questioned, “where is the concentration or recognition of schools that focus on the whole child – or broader skills in music and the performing arts?” They argue that the OECD is simply concerned with producing economic “robots” rather than fully developed young adults – and the cost is any interest in developing the whole child.

Other criticisms include that:

- Pisa is creating an escalation in standardised and reliance on simplified data that doesn’t bare any relationship with the real world.

- It is encouraging short-term 3 year fixes when in practice genuine change to an education system takes decades

- PISAs testing is narrow, “dangerously narrowing our collective imagination regarding what education is and ought to be about.”

- The types of children PISA tests are creating are less children than economic units.

- PISA is compromised and not neutral. It is claimed that it is designed to work in the interests of lobby groups and big business who gain financially.

- By pushing more and more testing into classrooms, teachers are being forced to teach lessons by rote, “turn learning into drudgery,” gear education entirely to the needs of improving scores with impacts on the wellbeing of students and teachers – and in all these ways the OECD is “killing the joy of learning.”

- In reality not every student in each country performs the same test. In practice, rather, students actually answer less than half the reading questions, and the national ranking is extrapolated from a mathematical model that calculates what students might have scored if they had answered all questions. Prof Svend Kreiner, of the University of Copenhagen, estimates that, as a result, reading scores introduce so much uncertainty that actual league table rankings could vary by 20 places or more – rendering them practically, at kindest interpretation, misleading. He also writes that it is self-evidently “meaningless to try to compare reading in Chinese with reading in Danish [or any other language].”

A group of eminent experts drawn from across the educational sector worldwide signed a letter in 2014 to Dr Andreas Schleicher, director of the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment, stating:

“We are deeply concerned that measuring a great diversity of educational traditions and cultures using a single, narrow, biased yardstick could, in the end, do irreparable harm to our schools and our students.”

The SchoolsCompared bottom line.

First, whatever the merits of PISA, the UAE government has given itself an incredibly difficult and ambitious goal to meet the target it has set itself to be a top-20 PISA country..

This is not because what the UAE government is doing to improve education is not impressive, or having an impact, or lacking in creditable ambition – actually we think the Dubai (KHDA) and Abu Dhabi (ADEC) Inspectorates in particular are achieving at world class levels in their school inspections and, as importantly, the planning advice and training they are giving to schools to follow up each Inspection.

It is simply that, we believe 2021 is a very short time frame for the changes required to be implemented – and felt. It will, we believe, take around a decade for the actions of the Inspectorates to improve schools to be represented fully in PISA scoring.

This means that we do not think parents should take the next round of PISA scoring as definitive. What is helpful, however, is for parents to recognise that our best schools are teaching children at a very high, globally competitive standard. Equally, our worse schools are not. Arguably we did not need PISA to know this.

Second, we believe that PISA is too narrow a way for parents to judge UAE education as a whole, or make absolute decisions for which curriculum school to choose for their children. The Canadian curriculum, for example, tends to score highly in PISA, but for entry into top tier UK universities it is high scoring in A Levels and the IB that hold greater weight. It is about context too – a properly accredited High School Diploma will carry more weight for many employers in the US than either A Levels or the IB simply because it is more recognised.

This said, statistically both IB and British curriculum schools perform well in PISA – and significantly higher than other curriculum schools. If context is right, there would seem no harm in parents prioritising either of these curricular. However, many Indian, and indeed Arabic, Canadian, Japanese – the spectrum of parents from different cultures – will take the view that the culture of the school is every bit as important as the global value of the qualification their children are eventually awarded (let alone the PISA scoring).

Thirdly, employers and universities are simply not asking applicants about PISA. For Universities PISA is very much just one of a number of background issues taken into consideration when they look at setting the grades required for entry into any given degree program. Arguably, however, other factors are taken more seriously. For example, concerns with grade inflation at A Level have been seen to have influenced universities to lower the threshold entry requirements for many IB students.

Our bottom line for these reasons is that parents should not unduly focus on PISA. It remains, we believe, far more important that parents continue to visit and question schools in the following key areas:

- Asking for the destinations of their students when graduating. What percentage of students go to University and where – and how many school leavers secure employment in industry, and in what positions.

- Asking schools if and how they measure added value. All schools should be measuring this. For example, in UK schools, prospective parents should ask about Progress 8 or equivalent. Prospective parents should ask how many children at the school meet their projected flight paths, how many do not, and how many exceed them. This is a key measure of how children are performing for all children regardless of ability.

- Asking schools for a breakdown of examination results for all children, and asking them to include any children that are not entered for examinations in any subject.

- Seeking the views of parents at the school where possible. Many schools will introduce you to other parents if you do not have knowledge of these directly.

- There is no short cut to visiting schools. Always try and meet with the subject teacher that is likely to teach your child in his or her favourite subject.

- Questioning schools about their level of teacher turnover for the last three years. In the Emirates this can be high. However, if it runs higher than an average of 15% over three years, ask “why?” Teacher retention is, we think, a critical indicator of a school’s stability and ability to provide continuity of teachers for your children. Changes to teaching staff has very negative impacts on a child’s education. Schools that invest in the professional development of their teachers and their conditions of employment are likely to have teachers that have the capacity and passion to invest in your child(ren).

- Referring to whichschooladvisor.com and schoolscompared.com to gain independent views from different experts on your given school. Both sites integrate feedback from parents and teachers without filtering from schools.

- Use the KHDA and ADEC reports. These are very considered and impressive. Take care to look at the detail, as these reports are at their most valuable, in many cases, when you look at the detail, rather than overall score. For example, many schools find it hard to meet the standards expected in Arabic subjects and this will pull down their score. As parents it is important to weight this, and other areas where a school may perform less well, in your evaluations.

- Finally, and as importantly as all of the above, interrogate schools about their views on the “whole child.” What investment is made in ECAs. How much time in school is given to children to explore their own interests and passions within the timetable? What range of activities is made available to children outside academics – and how many children take part.

PISA, in summary, is certainly important. BUT, we believe, it should be only one amongst a number of measures that any government should include in its planning – and arguably not the most important one. Where are the league tables for the development of the whole child in PISA? The answer is, bluntly, nowhere in sight.

It is worth finishing with what we think is an excellent summary by Iain Colledge, Principal, Raha International School, in a paper written for BIS:

“Does such a narrow focus on results and league tables come at the expense of children’s long-term development? Never have countries relied so much on a single, globally adopted measure, and never has there been so much time, money and energy spent on “rectifying” low or falling positions in the Pisa global league table. But is it worth all the fuss? And how are British international schools affected?

There is a hidden [negative] cost for thousands of children whose governments see a high ranking in Pisa as the pinnacle of modern education.

Education is about developing academic ability but it is also about so much more. It is about helping children to become good citizens, problem-solvers, communicators, leaders, and to value empathy, compassion, determination …. Schools should be happy places, where children can thrive in a positive environment.

Sadly, some of those countries that achieve highly in Pisa also exhibit some worrying trends. Arguably, it is down to cramming, pressure and long days for those children for whom results mean everything. For many nations this “progress” has aided the rise from developing nation to economic powerhouse, but can this focus solely on academics continue?

What British international schools do best [in the UAE] is to develop rounded children who are well educated but who also developed the wider skills and experiences required to be successful adults.”

Updated January 2017

Leave a Response