The Big Read. Where are all the Books? Teaching the Arabic Language in UAE Schools and the End of Wishful Thinking. The SchoolsCompared Guide.

Background. Where are all the books? Teaching the Arabic Language in UAE Schools and the End of Wishful Thinking.

There is a Problem and we need to Stop Pushing it under the Carpet.

How do we bring Arabic alive for children in our Schools? Where are the Books to Inspire Them?

Despite the official mandate to include Arabic as a required language for all UAE students until at least the age of 13, the uptake in demand for Arabic books by students is absurdly underrepresented when compared with that for its English counterparts.

Our last article outlined some of the reasons why Arabic, as a subject taught in our schools, has not always been held in the highest regard by young people – and looked at why they are struggling.

More here.

We found the reasons why students struggle to learn Arabic, whether reading or writing it, are legion – but disagreement on how to actually translate books accurately and inspirationally, and the resulting lack of almost any books to wow children, must both take a fair share of the blame for what we must now recognize as a failure. This is absolutely not a failure of our schools, or our teachers. The problem is much deeper and more serious. The system is structurally configured to make children fail.

And we also argued that it does matter, really matters – not only for Arabic children, but all children who have been given such an extraordinary opportunity in our schools to learn one of the world’s most expressive and beautiful languages.

If there are no, or very few, inspirational books for them to read – just how on earth can we expect them to excel?

So where, exactly, have all the Arabic books gone? Why when we visit school libraries, almost without exception, are we struck less by the wow of Arabic books than a desperate disappointment. Frankly, the experience of visiting the majority of Arabic libraries in our schools, relative to their English counterparts, is an upsetting, dispiriting and depressing one.

What is going wrong?

The Power of Reading – in itself and as the heart of learning a language.

Reading is fundamental. The average CEO reads upwards of 60 books a year. In the face of a Covid 19 pandemic that is making us think again in so many areas of education, the one thing that no one disagrees on is the centrifugal importance of books and reading.

In a typical UAE school library, and no one likes admitting this, you will struggle to find many, if any, genuinely exciting Arabic titles, or English titles translated to Arabic. The point is that you can walk into some schools with well-stocked Arabic libraries. But only well-stocked in terms of the number of books. And that is not meaningful – least of all to the children and students we need to inspire.

Turgid, uninspiring books are worse than torture for the best of us – and actually bring our culture, history and the beauty of our language into disrepute. When reading works best, it does so because it pushes us emotionally and intellectually to question the world and ourselves, it ignites our passions, makes us think and feel.

Pictures tell a thousand words

Let’s be honest too. What on earth is going on with the majority of Arabic book covers? Even with books in translation, we seem to take fabulous English language covers and turn them into something alien, often crushing the life out of them in the process.

Countless research has been poured into the effects of visuals on the ‘pleasure centres’ of the cognitive mind. Although you never judge a book by its cover, strong visuals and cover art are lacking to say the least for many translated and original titles.

This is a major obstacle or barrier when trying to attract a young audience. Why do publishers invest so much in the design of book covers in the English speaking world if they did not play such a vital and powerful role in attracting readers? Why in the Arabic publishing world do we seem to deliberately do exactly the opposite with our books? What is the point we are trying to make? Sometimes it seems that the Arabic publishing world is deliberately undermining itself. At the least, it is probably fair to say that the vast majority of traditional Arabic texts, including those targeting audiences, lack imagination in their covers.

The Views of those on the Front Line with our Children.

We consulted widely in writing this article, but it was telling that many (the majority) of those we did contact felt wary of putting their views into the public space. Few wanted to be placed on the record, despite their frustrations.

We did, however, find a number of leaders courageous enough to speak out, share their experience and give us an honest insight into the challenges and reality of Arabic language teaching and reading in our schools.

Alan Jacques, Head Librarian at Gems World Academy and the 2020 UAE Librarian of the Year told us:

“We do need more contemporary youth fiction in Arabic. However, some of what is available is attractive to readers. What we need to now achieve across schools is to see these curated titles on display in the same ways that we highlight English books”

For Mr Jacques, schools have a role in in creating inspiration Arabic reading spaces that appeal to all readers. Creating reading spaces that are a destination for children is one way of addressing, if cosmetically, the broader more complex issues of Arabic book availability and quality.

This may well mean thinking bigger than placing Arabic books in a traditional library. Arabic books, rather, could be the heart of inspirational meeting places in schools – places that children want to visit.

Mr Jacques also believes that we may be missing a trick. Too often schools focus on a set of core titles that meet the needs of representing the historic canon of Arabic literature – this regardless of their relevance to young people. Of course, these books have a role, just as Shakespeare has a place in every English library. But it is not, and should not, be the beginning and end of what libraries offer children. Mr Jacques argues that comics have an enormous capacity to inspire readers across ages and inspire both a love of reading, comprehension, and vocabulary development:

“The same theory, of making reading spaces attractive to children, can be applied to comics. In comics, the pictures bring the words to life. It becomes a moot point that the text language is in Arabic.”

The net effect, however, of a child reading an illustrated novel or story in Arabic is that they pick up the language … become inspired by it. Counter-intuitively, snobbishness in the types of books we make available to children in their learning journeys only serves to damage their life chances and undermines the Arabic language learning we are all so keen to inspire and secure.

Mary Rose Grieve of Hartland International School, and School Librarian of the Year 2019, agrees:

“The Arabic picture-book market is thriving thanks to publishers such as Kalimat who produce high quality books with lovely illustrations.

The written Arabic is easier to read and therefore more accessible to our students, many of whom are learning how to read Arabic for the first time in school.

These books are much more popular.

It is lovely, through these books, to be able to encourage children to read Arabic books with their parents.”

More on Kalimat books can be found here.

Creating literary ‘eye-candy’ is no easy feat. It is also expensive.

Positively, however, this is a high growth segment of the publishing industry for both Arabic children and their second language brothers and sisters.

Certainly, this is an area in which there is demand for graduating students in art to make their mark in industry.

The fundamental lack of supply to meet demand

International schools in the UAE, whether UK, IB, American, Indian or any number of alternative curricular founded schools, inevitably rely heavily on their Arabic teaching staff to support the sourcing and procurement of Arabic books.

But….. this may not always be the best approach. This is a hugely sensitive area, but we do need to recognize the unspoken truth, the giant elephant in the room, that, faced with the demands of the Arabic curriculum, there is pressure on many Arabic Departments to focus on, even limit, reading resources to the classics.

It is the safest approach.

Classical Arabic does not risk confusing children with mixed messages, does not bring confusing moral and cultural messages, does not inflame the ire of traditionalists – and if the price to be paid is a lack of interest of children in reading or learning Arabic – for many departments and traditional teachers, so be it. If the price to be paid is to teach children by rote rather than through inspiration, so be it.

Many teachers of the classical language, following strict guidelines, will understandably stick with the Arabic classics. The curriculum, they argue, does not give them the time or freedom to experiment. Many speaking with us did not feel empowered to choose books that they believed would inspire children, either because of the risks that they saw as coming from this, but more often because of their need to sediment classical Arabic. The joys of colloquial Arabic, within the current Arabic curriculum, must be reserved for much later in their lives when children have left school and have the basics.

The problem, of course, with this approach, is that learning by rote no longer conforms to any accepted metric of good teaching practice. Providing children with books that have no relevance or meaning to a majority of the 200 plus nationalities in the UAE makes absolutely no sense beyond this very narrow view of the role of Arabic language teaching in schools. In fact, it completely undermines it on its own terms.

The reason why schools do not broaden their choice of books for children, however, is much more complicated than even this:

“We spent a lot of time scouring the Arabic publishing industry. We have had to search in Egypt, Jordan and Lebanon to boost and bolster our collection.

Arabic has a long and proud history of literature — yet lacks significant new literature.

Even when we have sourced books that we believe would have a profound impact on teaching Arabic and brining the language alive for children in our schools, in many cases we also found no one interested in, or supportive of, actually importing them into the UAE and making them available to children.”

Alan Jacques. Head Librarian Gems World Academy. UAE 2020 Librarian of the Year.

Hartland International School has witnessed a more positive trend:

“There has been a real upsurge in publishing Arabic children’s books, and we have Harry Potter and the Wimpy Kid books in our library, as well as translations of books by Lauren St John, amongst others.”

Even here, however, there remain structural issues:

“As almost all the children in our school find reading English at this level easier than reading Arabic, they are not often borrowed.”

Mary Rose Grieve. Librarian. Hartland International School. UAE Librarian of the Year 2019.

If there is a lesson to be drawn here, beyond the structural problems of supply and demand, it is surely that even the most relevant Arabic books need to be given a context in school life within a destination that children want to visit, supported within the curriculum and, where possible, beautifully illustrated.

The rules of supply and demand apply as much in publishing as other areas of life – publishers will only produce content in areas where there is demand.

However, not so fast. That demand could be created by schools, working together. Schools have the capacity to create demand by placing books on the curriculum. The point is which books they choose. If Harry Potter, in Arabic, was placed as a core text in the curriculum across schools, parents, en masse, would buy it. That is a decision. Defeatism in the face of supply and demand issues is not a given that is so easily justified.

Of course,

“… unless there is a substantial market bringing ‘big dollars,’ book publishers are only interested in bringing the prominent and ‘big’ sellers.

Even though reading is in a dire state and literacy is a huge thing on the UAE’s agenda, no one is putting their money where their mouth is.

This is why we have had no choice but to go outside of the country and import books ourselves.

That says a lot and should be sending alarm bells across those with an interest in the effective education of children.”

Alan Jacques. Head Librarian Gems World Academy.

Those with an interest? Is that not all of us?

Lacklustre demand may also be a result of presenting ‘dumbed down’ literature to weaker readers of the Arabic Language:

“In the old days, teachers would give struggling readers a childish book so they could read the language.

The problem with this approach is that often the subject matter of these books was so condescending that it only served to deepened a child’s dislike of reading.

Now we do have Hi-Lo books, which offer readers mature age topics but with especially designed text for struggling readers.

However, these are only now starting to appear in Arabic.”

Alan Jacques. Head Librarian Gems World Academy.

Lack of demand from students, weak engagement from parents in the selecting and reading of Arabic books, almost no financial incentives for publishers to source content – and lack of investment in creating destinations in schools for Arabic reading, and a fear of diverting from classical Arabic …. all play a part in the current state of Arabic Books in UAE schools.

Other barriers for sourcing quality Arabic literature

Some argue too, that even translated popular books in modern literature will still be too hard for students to get to grips with:

“Reading translated books would not be easy for Arabic B students.

The literary language won’t be one of the top interests for a non-Arabic speaker while being exposed to Arabic language.”

Ms. Maram Juma, Arabic Teacher. Universal American School (UAS)

No doubt, there is truth in this. However, surely working through translating Harry Potter in class with the English source material is going to be infinitely more inspiring to children than current alternatives? The further value of this lies too in the many questions of translation that will be thrown up by the process – this arguably both intellectually and educationally important in its own right.

Even more controversial, several other issues have further impacted on the quality and availability of Arabic Books. The most significant of these is censorship.

Censorship has, of course, had both a positive and negative impact. Positively, through censoring certain aspects of texts, subjects and books can be made available to students outside the age appropriate level of the original text.

But this issue arguably only arises when there are not enough books to provide relevant age appropriate resources to children at each stage of their learning journey.

Censorship on these grounds only feeds the problem of a lack of worthwhile available books rather than solves it.

In other areas, censorship is more complex:

“No one can say: ‘No, we have an absolute freedom and no book should be censored’

This is because censorship works in positive and negative ways at the same time.

It depends on context; of what you think and why, and what the government’s vision is at that point.”

Dana Khaldoun Saadeh, Instructor at Qasid Arabic Institute, Amman Jordan.

“There are, as you would expect cultural issues when translating literature from English into Arabic.

In a memorable review on medium.com, Syrian scholar Wafa Dukmak runs through the various references in the Arabic translation of Harry Potter that had to be amended and/or deleted which include references to alcohol, kissing, houses and the fact that children in the Arab world are generally unfamiliar with the concept of a boarding school.”

James Mullan. Founding Committee Member and Director of Communications for the Emirates Airline Festival of Literature. Co-founder. SchoolsCompared.com, WhichSchoolAdvisor.com.

Another factor is the history of the Arabic language and the chasm between the spoken and written word:

“As you know, Arabic has a much greater oral tradition than a written one.

The spoken language is so different to the written one.

There are, because of this, significant challenges in trying to embed a reading for pleasure culture amongst our Arabic community.”

Mary Rose Grieve, Hartland International School.

Mrs. Grieve spoke with us at length of resources, particularly for Muslim students, that she believes would be ideal if translated to Arabic:

“There are some fantastic books about Muslim children published in English.

Planet Omar and Little Badman are two excellent examples.

It would be great to see these in Arabic.

I am hugely supportive of Arabic authors who write in Arabic; their readership need to see themselves represented and reflected in the text.

They are fantastic role models for our Arabic students.”

Once again, it is evident that sourcing, displaying, and promoting quality Arabic books for our students is an uphill battle for all educators in the region.

Finding solutions. What can we do together to address the issues moving forward?

If these are the challenges and gaps in the system, there are positive solutions.

Top Tip 1: Use Arabic Picture Books to bring the Arabic language alive

Mary Rose Grieve, Librarian, Hartland International School recommends this resource for picture books for children and young adults.

This collection of recommended books has been compiled in conjunction with publishers to ensure availability and segments books by appropriate age levels.

The site can be partially accessed in English (Top left hand corner, country flag.)

Top Tip 2: Focus on Arabic primary texts

Ms. Maram Juma, Arabic Teacher. Universal American School (UAS) is more insistent on the importance of focusing on Arabic literature rather than translations of books written in other languages:

“We need to focus our Arabic speaking students on the importance of Arabic literature.

This is because we can find, in Arabic primary texts, recognized shared experiences in the writing.

The novels of some famous Arabic authors have been translated into different languages. From these I would recommend works by writers including Ghassan Kanafani, Al Tayyeb Salih and Jabra Ibrahim Jabra.”

Top Tip 3: Reading with our Children

As parents we can make a difference:

“A key issue regarding children’s literacy in Arabic which has been identified by many experts is the lack of a parental reading culture throughout the Arab world.

By parental reading culture we specifically mean parents reading to and with their children.”

James Mullan. Founding Committee Member and Director of Communications for the Emirates Airline Festival of Literature. Co-founder. SchoolsCompared.com, WhichSchoolAdvisor.com.

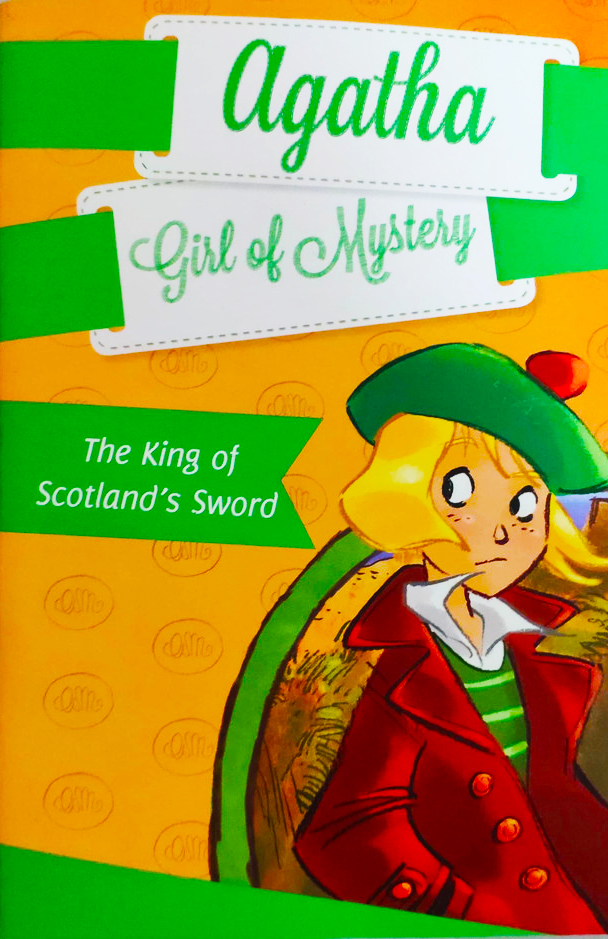

Top Tip 5: The Books that Really Work to Inspire Children

Alan Jacques, Head Librarian, Gems World Academy recommends the following books as tried and tested by students within schools:

Translated Titles

Agatha: Girl of Mystery Series by Stefano Turconi and Steve Stevenson (age 9+).

Abstract: This chapter book series stars Agatha, a hip and headstrong girl detective who travels around the world, solving exotic international mysteries with her cousin Dash.

Buy it? Here.

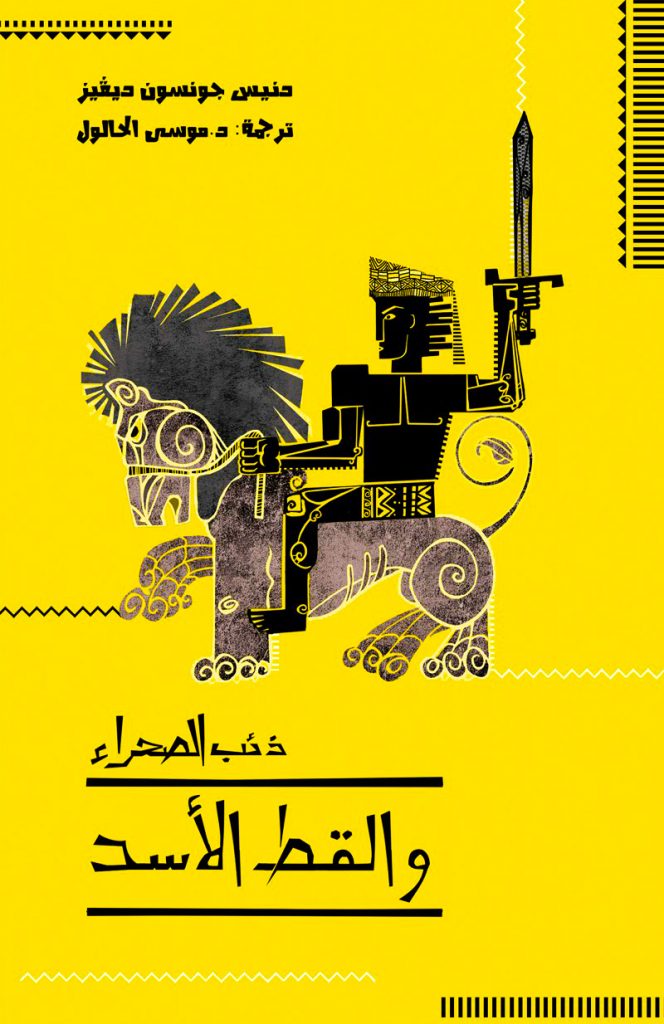

The Desert Wolf Series by Dennis Johnson Davis (ages 10+).

Abstract: A four part series of adventure and exotic fantasy.

Buy it? Here.

Buy it? Here.

Buy it? Here.

Buy it? Here.

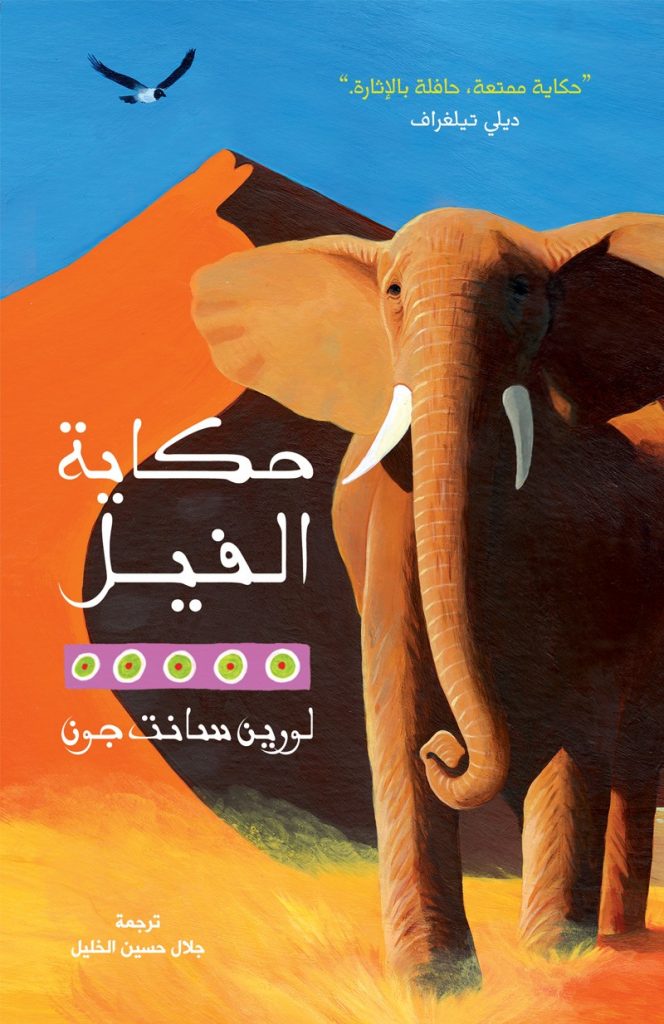

The Elephant’s Tale by Lauren St. John (age 10+)

Abstract: When a sinister stranger threatens Martine’s home at Sawubona Game Reserve and her beloved white giraffe, she is determined to try everything to save them. To do that she and her best friend must risk their lives by traveling to the Namibian desert. There they uncover a plot so terrible it threatens the existence of every person and animal in the land.

But it? Here.

Haunted, by Reem Gazal (age 11+)

Abstract: A young adult story that takes place in a palace rumored to be haunted by the Jinn. This rumor prompts a group of young men to take a risk and visit the place to investiage for themselves the matter.

Buy it? Here.

Original Arabic Titles:

لغز صورة من الكوكب الاحمر

English Title: The mystery of the Red Planet

Suitable for? Age 11+

Writer: Mohammed Alhamadi

Abstract: When the civilised world unites, and the only goal of science becomes to increase profits, people dreaming of another world, full of good and beauty, are emerging from the world of hatred and all that can lead to war.

Buy it? Here.

نورسان سوترا

English Title: Norsan Sotra

Writer: Asma Qudri

Suitable for? Age 13+

Abstract: The leader and protector of science and power tries to balance the World between good and evil. Can he succeed in creating a just society?

Buy it? Here.

ارواح كليمنجارو

English Title: Kilimanjaro Spirits (age 14+)

Writer: Ibrahim Nasrallah

Abstract: A group of desperate individuals, two of whom are Palestinian adolescents who have lost their legs in during military strikes, are preparing to climb Mount Kilimanjaro. They have nothing–and everything–in common. Hailing from Palestine, Lebanon, Egypt, and America, the characters test the limits of their physical and emotional strengths to prove to themselves that they can transcend their strife-ridden histories and accomplish the unexpected.

Buy it? Here.

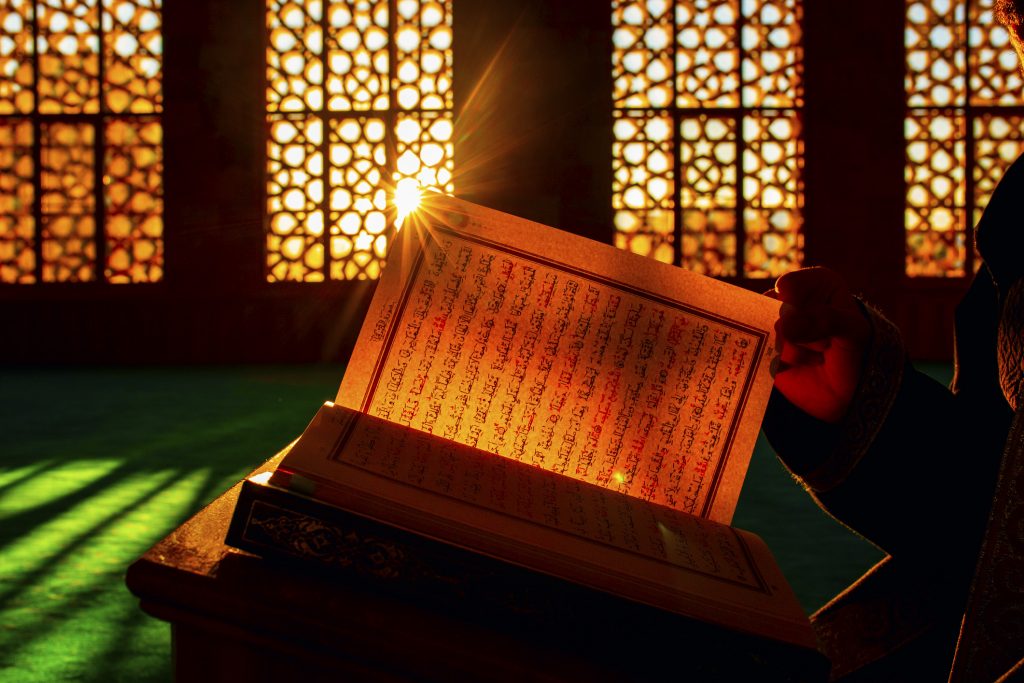

Alternative viewpoint: Teaching Arabic without the context of the Holy Quran is doomed to failure.

Professor Mamdouh Mohamed, Former Bilingual School Inspector, Dubai Schools Inspection Bureau (KHDA) argues that we are looking in the wrong direction.

To really have impact, and to build the bridges between the Arab and Non-Arab world that Arab and non-Arab families prize equally, we should instead be introducing the Quran into Arabic B for non Arab, second language students.

Professor Mohamed believes that trepidation in doing so, whilst understandable, effectively leaves non-Arab students with a major gap in really coming to grips with the underlying framework of the Arabic world – one that pervades literature, schools, government and family life. Without this, any learning of the Arabic language can only ever be skin deep and without depth or context.

Despite the separation of church and state in most Western countries, Professor Mohamed argues, it is not uncommon for international schools to study the bible and, in many British curriculum schools too, for example, within the context of Religious Studies, the Muslim faith, as other faiths, are also studied:

“The UAE mandates Islamic Education for all Muslim children, but perhaps incorporating the Holy Quran as a literature piece for Arabic B students could be equally beneficial on their linguistic journey.

The main obstacle for Arabic learners is not a matter of speaking a wide range of Arabic dialects.

The true problem is when we find our children not understanding the Quran.

Let us focus our efforts to address this problem.”

Professor Mamdouh Mohamed. Former Bilingual School Inspector. Dubai Schools Inspection Bureau (KHDA)

Professor Mohamed also believes that Arabic departments should do far more in introducing sources other than books and educational literature to bring the language to life. By logical extension this might include films, music and bringing speakers into schools to help bring books, including the Holy Quran, with all their underlying cultural context, to life for children.

This stress on Arabic context is reflected by Ms. Maram Juma, Arabic Teacher. Universal American School (UAS):

“I personally think that non-Arabic speakers need to have books written from the reality of Arabic culture. There is a lack of these books in our schools.

I believe that investing in educational resources has been far too limited in the Arab world.

We need, for example, something like IB Inthinking.

Ms. Maram Juma, Arabic Teacher. Universal American School (UAS).

Bottom line? The SchoolsCompared.com Verdict on Teaching Arabic Language and Reading in UAE Schools 2020-21

The underlying truth that runs through everything in this world, is that solving this problem requires investment. What we need, what our children need, are individuals, governments- and publishers, willing to invest in translating books into the Arabic language and supporting the broader availability of Arabic titles and authors.

For the former, the New York Times best seller list would be a good place to start. We also need investment in translating the canon of English, American and broader international literature written for children and young adults.

There are many high net worth individuals who do so much for charity, but the force for good that books deliver has played second fiddle, understandably, to the more immediately gut-wrenching injustices and natural disasters of the modern world. But books promise long term solutions to our world – investment here promises a transformation of the linkages between the Arab and non-Arab world. Books have the promise of building a great bridge between East and West – and we have, today, in the UAE, children learning our language and ready to build those extraordinary bridges of the heart and mind. Surely, we must, however, give them the bricks and tools to actually make this meaningful and real. Currently they simply do not have access to the resources to do much more than dream them.

There is no doubt that the vision in the UAE for Arabic in schools is profound. It is equally true that the stakes are high – and the rewards for getting this right beyond price. However, the brutal reality is one of economics and a need for investment inside and outside schools. A coordinated effort to improve the landscape for Arabic literature in schools is needed; progress in Arabic language teaching will not happen by itself.

“The lack of appropriate material in Arabic has obviously been a major factor. Moves have been made over the last 20 years to address this. We can take, for example, the Kalimat publishing house set up in 2007 by Sheikha Budoor Al Qasimi in the UAE which has attempted to tackle this head on. But it is a huge task. More needs to be done – and it requires governmental intervention and support.”

James Mullan. Founding Committee Member and Director of Communications for the Emirates Airline Festival of Literature. Co-founder. SchoolsCompared.com, WhichSchoolAdvisor.com.

What does this mean in practice? Schools, government, publishers, students, industry, influencers and parents need to work together. Delivering to our children quality books, local and translated, rich in illustrations, in multiple forms of media across a variety of physical and digital sites – and in places within schools that children want to be and engage with – this should not be beyond the wit of men and women to deliver. It can happen.

Some schools are achieving against the many, many odds.

It is worth quoting, in conclusion, from an open letter sent to us by Simon Herbert, Head of School/CEO: GEMS International School, Al Khail:

“At GEMS International School (GIS) we recognise the value of reading in one’s home language. Not only does it allow one’s heritage and culture to be maintained, but it also […] promotes in-depth discussion and deeper thinking from students of any age.

Therefore, our students, from 85+ nationalities, are encouraged to read and share regularly in the classroom.

Arabic is the home language of many students in the UAE, and at GIS we are determined to allow enriching reading opportunities to abound in both Arabic and English.

We also know that those learning Arabic as a foreign or second language will benefit hugely from plunging into Arabic and discovering the joy of reading a ‘difficult’ language. It grounds them in the culture of the wonderful nation that is their current home.

How do we make this happen?

To support this, our students, and their parents, have been encouraged to join our ‘Arabic reading month’, leading to World Arabic Language Day.

We have provided Arabic apps, which are aligned to our International Baccalaureate Programmes and levelled according to age. These apps cover several fictional genres, but also topics such as health and the environment.

Our students in Grade 5 are now acting as ‘reading buddies’ (even virtually) to Grade 1 students, which inspires the little ones!

We have also introduced quizzes, book reviews, reading ladders, competitions (such as ‘take a photo of yourself reading in a variety of locations’) and certification from leaders to encourage reading regularly.

We have to be persistent and determined in our quest to enhance Arabic reading levels and instill the joy of reading in native and non-native speakers of Arabic. There are several obstacles and challenges to overcome, and not only from YouTube, Instagram and the myriad other online distractions for our young people!

[Many] of the children’s favourite books in English are not so readily available in Arabic.

- Lilya in Grade 5 wishes she could find more Roald Dahl in Arabic, particularly her favourite, ‘Charlie and the Chocolate Factory’.

- Goregio in Grade 4 wishes he could find ‘Toy Story’ and more books that he knows already, to make his reading more fun.

We also carried out a survey and 200 children responded. Of these, popular choices for wish list books were:

- the Harry Potter and Percy Jackson series

- ‘Elephant in the Garden’ or anything by Michael Morpurgo

- ‘Lord of the Flies’ by William Golding,

- Marvel comics and graphic novels including Manga

- Classic poetry

- Philosophy such as ‘Sophie’s World’ by Jostein Gaarder,

- David Walliams’ ‘Billionaire Boy’; and, for younger readers,

- ‘The Very Hungry Caterpillar’ by Eric Carle and ‘Brown Bear Brown Bear What Do You See?’ by Bill Martin Jr.

Mrs Mustahsen, mother of three and an Islamic B teacher at GIS, has noticed that the range of exciting children’s books is narrower in Arabic.

She has been searching for graphic novels and books on ‘Batman’ and ‘Star Wars’ and even ‘Diary of a Wimpy Kid’.

She comments that the books most relevant to their lives are:

“simply not available in Arabic.”

Another challenge to overcome, when seeking translations of well-known English language books, can be the translation itself.

Is the translated book as exciting as the original? Is the tone and atmosphere as engaging as the original source text?

One of our parents found that the book she had enjoyed in English by John Gray, ‘Men are from Mars, Women are from Venus’, did not capture the same ‘feel’ as the English version at all, and she noted that some of the translated words ‘were not suitable.’

It is crucial that translations are precise, relevant and meaningful, especially as Arabic can be viewed as too hard in the first place.

From our student survey, the main reason for selecting an English book over an Arabic version or Arabic original was simply the ease in the language.

Interestingly, even some first language Arabic speakers comment that reading in Arabic requires more concentration.

Therefore, every effort must be taken to facilitate student reading in Arabic. This includes making sure they have an excellent translation, podcasts, simplified versions and even an attractive book cover. Whatever it takes to bring books to life.

Almost 70% of our student respondents commented that cover art on Arabic translations should be more enticing to attract the reader. Given that almost 76% of students agree that ‘translated books from English encourage students to read in Arabic’, we at GIS have also organized a cover art competition, linked to our Art department, with the aim of enticing the reader to pick up an Arabic translation in the first place.

On the positive side we have, too, seen success stories.

One book from the Mohammed bin Rashid Space Center so inspired our students that it was read over and over again last year. The book contains clips from comics and different activities in both Arabic and English. This does prove that with enough thought and planning, children will enjoy reading in any language.

With such a rich history and culture on their doorstep, we are determined that our students will discover the joys of Arabic and, with persistence and support, a door into a new world of literary marvels.”

Simon Herbert. Head of School and Chief Executive Officer. GEMS International School Al Khail, Dubai Hills.

It is just this sort of thoughtfulness, passion and creditable investment in teaching the Arabic Language in UAE Schools that should give us all hope.

Just imagine if this investment was matched by the might of the publishing world to support them.

In Dubai they say if you build it, they will come.

It is surely time to start that building.

Our children, from East and West, cannot afford to be kept waiting much longer ….

Notes from the Editor

- Many thanks to all those who contributed to this article. Particular thanks must go to the Heads of Arabic at both GIS Primary and Secondary School, Mr Magid and Ms Amineh, for their valuable contributions. This article could not have been written without their considerable guidance and support.

Leave a Response